Book Review by Somdatta Mandal

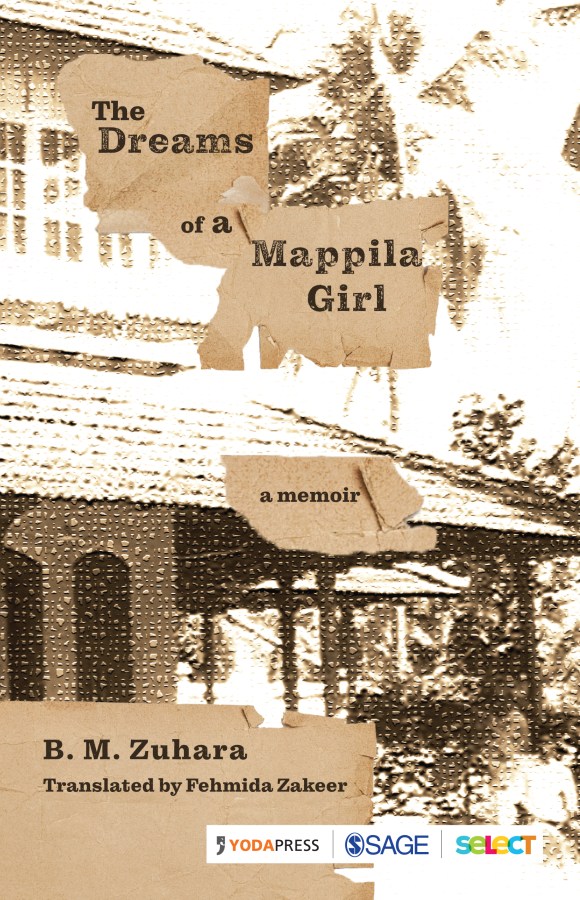

Title: The Dreams of a Mappilla Girl: A Memoir

Author: B.M. Zuhara

Translator: Fehmida Zakeer

Publisher: Yoda Press & Sage

The terms ‘autobiography’ and ‘memoir’ are sometimes used interchangeably but the former is more fact-based and tends to be historical, whereas a ‘memoir,’ derived from the Latin word ‘memorandum’, is chiefly a personal, minute recollection of events, not necessarily intending to cover a person’s entire life, but often written from an epiphanic perspective, a significant event, or a particular aspect of the memoirist’s life. Thus, memoirs are essentially subjective and can never claim to be bio-bibliographical narrations. B.M. Zuhara, the writer and columnist from Kerala and a Sahitya Akademi awardee who writes in Malayalam, had penned The Dreams of a Mappila Girl: A Memoir (2015), which was recently translated by Fehmida Zakeer to English. It traces the childhood years of the writer, growing up in the village of Tikkodi in rural Kerala as a young Mappila girl from the Muslim community in post-Independence India.

For Zuhara, the things she remembers from her childhood act as vignettes which we readers string together to form a wholesome picture of the feudal system and social issues that were significant in her mind as she was growing up in the Malabar Muslim community in the 1950s. The tenth and youngest child of her parents living in a huge ancestral house called Kizhekke Maliakkal, Soora’s narrative gives us details of the things she remembered about the place till the point where at the age of thirteen she moves with her family to live in a rented house at Kohzikode to be admitted in a high school and begin a new chapter in her life. But even after she gets admitted into a prestigious school at Kozhikode, uncertainty looms large over Soora’s life as her mother stays adamant about not allowing her daughter to wear a skirt as a uniform as mandated by the school. In the ‘Preface’, Zuhara mentions that her childhood ancestral home does not exist anymore, but its memory is so strong that it appears as a character in many of her writings.

From the very beginning of the memoir, we form a clear picture in our minds about the location of the house, its detailed set-up filled with characters of the extended family including servants and cooks who lent a helping hand to run it smoothly. Like many other narratives, food plays a significant role in developing the ambience of Soora’s household. We get details of the elaborate tea ritual every evening, the eating of pathiris soaked in coconut milk, the aroma of fried plantains and coconut residue that filled the air, the details of the betel leaf chewed by her mother and grandmother with their decorative boxes and copper spittoons, the attempts to hatch chickens from eggs that were undertaken in the storeroom, the rearing of hens and ducks and goats by her brothers, the midday meals offered in their village school which their mother did not allow them to partake considering that it was solely meant for underprivileged children, and so on fill up a considerable portion of the narrative. Apart from visiting the village fair, Zuhara recounts the social mores of the society she lived in and offers glimpses into the secluded lives of Muslim girls and women who, despite obstacles, made the best of their circumstances and contributed positively to their communities.

One significant point about the memoir is the presence of Soora’s mother throughout the narrative and the strong influence that she had over her. While growing up, Soora often accused her of not looking after her well because she was an unwanted child. A religious woman who prayed five times a day, she not only tried to apply the teachings of the Quran to her life, but also shared her newly acquired knowledge with the people around her. Any deviation from the traditional lifestyle was, according to her, punishable as an offence by Allah. A pampered cry baby who would often burst into tears for the slightest reason, Soora from the very beginning was a sensitive child, who was often admonished for her interest in playing with boys and learn Kalari Payattu like her brothers, play with them in the rice fields, stand on the bridge and listen to the songs sung by the farmhands as they worked. She was also scolded for eavesdropping into conversations made by adults and like all traditional Muslim women, her mother wanted to get her married at a very young age. The real and perceived slights that Soora was subjected to, were primarily targeted at her physical appearance, specifically her dark complexion and her tendency to cling to her mother. But paradoxically for a seemingly timid child, Soora’s propensity to constantly question what is established as normative behaviour for a girl earns her the nickname of ‘Tarkakozhi’ – one who argues. What these contradictory impulses perhaps reveal was a girl who was overwhelmed by the big and small battles she must constantly fight, a life burdened by gendered expectations, yet a girl whose deepest desire was to be like Unniarcha, a mythological woman celebrated for her fearlessness whose ballads Soora grew up listening to.

But soon Soora realised that some of her dreams would never materialise because of her gender. Certain details, such as that of Soora’s grandmother passing away at the age of thirty when Soora’s mother was fifteen; or that two of Soora’s sisters were married even before she was born, reveal the dark reality of women’s lives in those times. In the ‘Preface’ Zuhara categorically states:

“I grew up at a time when Muslim girls did not have the freedom to dream. When I started writing, I had to face a lot of criticism and threats, and I found many limitations imposed on me. Until then, only men had recorded the inner lives of Muslim women. Even though I could not comfort my sisters physically, I have tried through my writings to give them a voice by speaking about their dreams, chronicling the obstacles and difficulties faced by them, and providing a perspective from the point of view of women. In the process, I have tried to define a space for myself in the literary landscape.”

In her ‘Preface’, the author also wonders if her work is a “story, or a novel, or a memoir.” Her words became the wings upon which forgotten, and deeply bruised memories travelled out into the world. She recreated the stories of her dear and near ones around whom she had spent her childhood. She coloured her childhood experiences with her imagination and penned them all down. Even though all the names are of actual people, if she is asked if the stories are real or imagined, she can only say that they are both. So, she leaves it to her readers who have encouraged and supported her writing journey to decide.

Here one needs to add a few words about the translation. The translator Fehmida Zakeer also hails from Kerala and being a Muslim herself, her effort to make this book read as smoothly as the original Malayalam text is laudable. There is no italicisation of non-English words throughout the text and the list of kinship terms at the beginning, along with the elaborate glossary at the end, makes the book as reader friendly as possible while trying to retain the flavour of the original. The only occasional problem this reviewer faced while reading the text was that too many authentic words and salutary terms for relationships of even a single individual often turned confusing for a lay reader like her who had to pause and recollect who the actual person referred to was. For the protagonist, mention of Sora, Soora, Sooramol, and Zuhura is understandable, but addressing members of the extended family and others residing in the neigbhourhood in different salutations sometimes becomes difficult for people not acquainted with the South Indian Malayali culture. However, despite such a minor lapse, the book is engrossing and offers a wonderful slice of life of the rural and semi-urban Muslim community in Kerala, of its customs and lifestyle which otherwise would remain unknown to us in a muti-cultural and multilingual country like India.

.

Click here to read an excerpt from The Dreams of Mappila Girl: A Memoir

.

Somdatta Mandal, critic, translator, and reviewer, is a former Professor of English at Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL