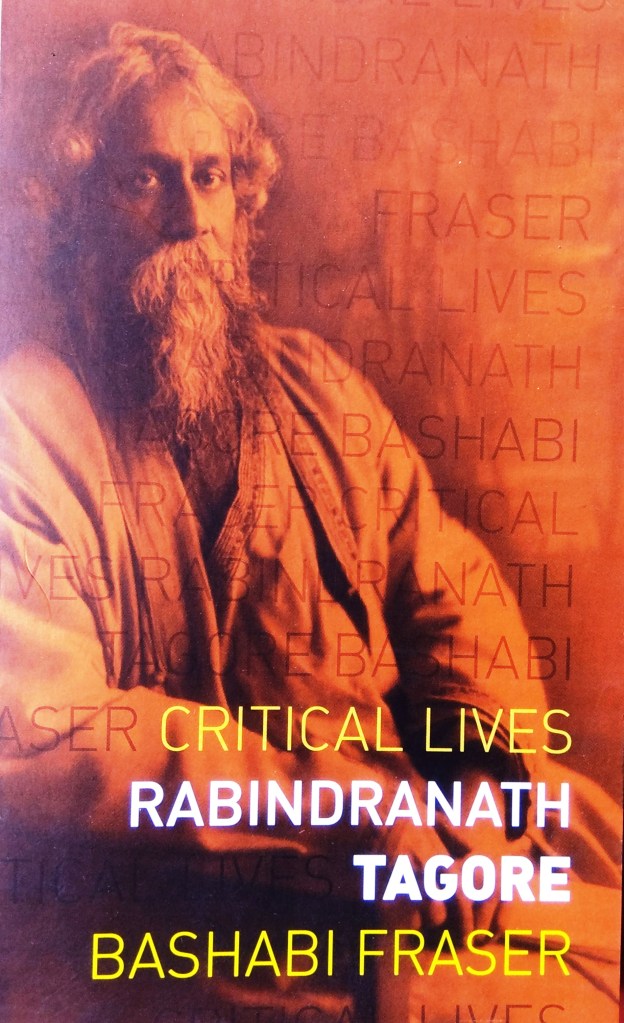

Book review by Rakhi Dalal

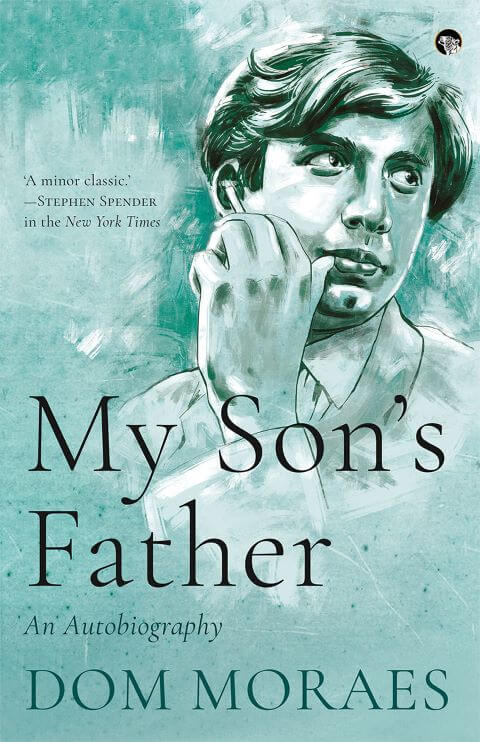

Title: My Son’s Father

Author: Dom Moraes

Publisher: Speaking Tiger, 2020

Dom Moraes (1938–2004), poet, novelist, and columnist, is seen as a foundational figure in Indian English Literature. In 1958, at the age of twenty, he won the prestigious Hawthornden Prize for his first volume of verse, A Beginning, going on to publish more than thirty books of prose and poetry. He was awarded the Sahitya Akademi Award for English in 1994. He has won awards for journalism and poetry in England, America, and India. He also wrote a large number of film scripts for BBC and ITV, covering various countries such as India, Israel, Cuba, and Africa.

“Between his Englishness and Indianness, the scales tipped to English.”

Wrote Stephen Spender in the Sunday issue of The New York Times on August 10, 1969 while reviewing My Son’s Father by Dominic Frances Moraes, an autobiography which was first published in 1968 when the author was only thirty years old. Spender’s observation came in view of the situation faced by writers of Indian origin writing in English in those times. He considered it fortunate that Moraes was brought up speaking English and not Hindi.

It is true that being born in an English-speaking Roman Catholic family of Goan extraction, the language came naturally to him and his affinity for literature sprung from his spending much time on reading books borrowed from his father’s library. Once he knew that he would be a poet, the decision to make England his home came logically to him. At one place in the book he writes:

“England, for me, was where the poets were. The poets were my people. I had no real consciousness of a nationality, for I did not speak the languages of my countrymen, and therefore, had no soil for roots. Such Indian society as I had seen seemed to me narrow and provincial, and I wanted to escape it.”

In this autobiographical account, a prominent role is given to the tussle in his mind, that kept him connected to his roots. This struggle, emanating from the memories of his early childhood years spent with his family and his relationship with his parents, is also the subject of this book. Interestingly, after this book was published in 1968, Moraes returned to India after spending nearly fourteen years of his life in England.

The book covers the period from his early childhood to when he became a father himself. The autobiography is divided into two parts with six chapters each. The first part titled ‘A Piece of Childhood’ covers the first sixteen years of his life with his parents. The second titled ‘After So Many Deaths’, deals with his own life, from leaving the house for London for further studies until he finds his place in the World. The thirteenth chapter is the Epilogue.

The name for first part is taken from these lines by David Gray, quoted on the title page:

Poor meagre life is mine, meagre and poor:

Only a piece of childhood thrown away.

In the first part, the choice of title reflects the content. For, it essentially deals with his troubled childhood years with a mother suffering from mental illness. He writes about witnessing the first signs of illness in his mother, about how his love for her first turned into indifference, then into anger and then cruelty with the passing years which were marked with increased incidents because of her illness which sometimes also posed danger to him and everybody around. Later when his mother was institutionalized, he blamed himself for it. However, it was the time spent with his father, reading, travelling and journaling, that made him turn to writing verses and to opt for living in London.

The narrative is enlivened by the keen and observant eye of a poet which missed nothing, whether it was the unsettling feeling of missing his father when he was a war correspondent in Burma or the joy of witnessing the beauty of nature. At such places, his poetic sensibility charms the reader and turns the reading experience into a joyful ride. His prose is lucid, interspersed with vivid imagery but with such a restrain that not a single word ever seems out of place.

Behind our flat was the Arabian Sea, an ache and blur of blue at noon, purpling to shadow towards nightfall: then the sun spun down through a clash of colours like a thrown orange, and was sucked into it: sank, and the sea was black shot silk, stippled and lisping, and it was time for bed.

The second part deals with his life at Oxford. His associations with poets like Stephen Spender, W.H. Auden and Allen Tate. He vividly portrays the English Literary scene of 50s London, bohemian life at Soho, his meetings with the likes of David Gascoyne, T.S.Eliot, Beat poets and Francis Bacon. He writes about his love affairs, about the kindness of Dean Nevill Coghill who always saved him from troubles at Oxford and about David Archer of the Parton Press who published his first poetry collection, A Beginning, which won him the prestigious Hawthornden Prize at the age of nineteen. But despite all this, he felt divided in his mind. Once while visiting parents of his friend Julian, he felt nostalgic.

It was a long while since I had been in contact with family life: it seemed familiar but distant, but snuffing at it as warily as the dachshunds sniffed at me, I felt a deep nostalgia for it. I thought for the first time in weeks of my mother and father and remembered the exact smell and texture of an Indian day. Driving back with my friend through the green and familiar landscape of my adopted country, I felt suddenly, and to my own surprise, a stranger.

Though he had put down his roots of work and friendship in London, where he knew he wanted to stay but there were moments, according to him, when some invisible roots pulled him to country of his birth. It was only around his twenty first birthday, while visiting his parents, he realised what it was. In a conversation with his mother, both of them wept in close embrace and suddenly he felt his troubles vanishing away.

I left India at peace with myself. Something very important to me had happened: I had explained myself to my mother, there was love between us, the closed window that had darkened my mind for years had been opened, and I was free in a way I had never been before.

The last chapter, ‘The Epilogue’, shows a thirty years old Moraes, a father to a newborn, finalising the manuscript of this book. For some reasons it doesn’t include his life events from the age of twenty one to thirty. As the ‘Epilogue’ closes, we see a father, pleased with his life, binding together the pages so that if his son reads them one day, he understands his father as the person he was.

.

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ . She lives with her husband and a teenage son, who being sports lovers themselves are yet, after all these years, left surprised each time a book finds its way to their home.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.