Sri Radha Canto 58

You are the fragrance of rocks,

the lamentation of each flower,

the unbearable heat of the moon,

the icy coolness of the blazing sun,

the language of my letters to myself,

the smile with which all despair is borne,

the millenniums of waiting without a wink of sleep,

the ultimate futility of all rebellion,

the exquisite idol made of aspirations,

the green yesterdays of deserts,

the monsoon in an apparel of leaves and flowers,

the illuminated pathway from the clay to the farthest planet,

the fantastic time that's half-day and half-night,

the eternity of the sea's brief silence,

the solace-filled conclusion of incomplete dreams,

the dishevelled moment of an awakening with a start,

the reluctant star in the sky brightening at dawn,

the unspoken sentences at farewell,

the restless wind sentenced to solitary confinement,

the body of fog seated on a throne,

the reflection asleep on the river's abysmal bed,

the undiscovered mine of the most precious jewel,

the outlines of lunacy engraved in space, and

the untold story of lightning.

You have, my dearest, always suffered

all my inadequacies with a smile.

I know I am not destined to bring you back once you've left.

All I can do hereafter, till the last day of my life,

is to collect the fragments of what you are

and try to piece them together.

Sri Radha Canto 19

Come, take half

of the remainder of my life,

but fill every moment

of the half that is mine

with your infatuation.

Was the bargain unfair?

Then leave me with a single moment

and take away the rest of my life,

but like the sky,

fill the whole space

above that moment.

No, not like the sky.

Come closer and become the cloud

over my past, present and future

so that, when I touched myself,

I would touch the monsoon of your body.

Your sighs would breathe

the gale spewed by the despair

of a distant ocean

and, when I smile

and touch myself,

the gale would cease.

My lifetime,

unconcerned with its nearing death,

would everyday renew its pilgrimage

to the early years of your youth.

You would exist as a mass of blue

carved by my command,

or as the blue

of all my known, partly known

and unknown desires.

Since I always dress in blue,

you too must be blue.

How can you have any other colour when

it would break my heart

if you had any other hue other than blue?

Was the bargain unfair?

Then come, take away

even that single moment.

But do not bend down, look straight

into my eyes.

Meet the impudent traveller

who has passed through hell after hell

and, at the end of the very last hell,

stands under a kadamba tree

and awaits your coming.

Sri Radha Canto 25

It was a bad day yesterday.

My husband dragged me by the hair

and knocked my head against the wall

several times, and insisted

that I come out with the true account

of where I had spent the previous night.

It hurt for some time,

but when he began an inspection

of my body, I could not

hold back my laughter.

God, I said to myself,

what an imbecile I have

for a husband!

He is looking for proof

of my infidelity

in the body

and at daytime too!

Sri Radha Canto 61

Reports of your passing away

have reached us here.

Don’t count me

among your widows

or among those who carry your body

in procession.

Your body, mercifully,

Is far, far away.

In the parting of my hair,

the vermilion mark

is brighter than ever.

Now stop joking,

become the bridegroom,

and come.

I wear

the bride’s heavy silk

and gold.

My bangles tinkle

And snub all sandals.

You no longer are

anyone’s father, son, husband.

You are the pure naughtiness

of our last night together,

the voice

that teases me,

and the touch that breaks

the virginity of my loneliness.

Just when I would stop crying,

you will arrive and tickle

my lifeless longing

into unrestrained laughter.

When they deposit your body

on the pyre,

all that you ever meant to them

will be consumed by flames.

They would return home

and, a few days later,

would fill your absence

with thoughts of you

and a thousand other things.

My joy today

is uncontrollable.

If you had not died for them,

you would not have become

entirely mine.

Since everyone believes you are dead,

my journey to the riverbank

will now be without fear.

All claims to you are now void,

Except mine.

They will forget I was ever there

Or even know how I held on

To your glamour-doll shoulders.

I fold up

Under your common hand of desire

As you disable my jelly-limbs

Filling my spaces

Beyond all that exists

Or does not exist.

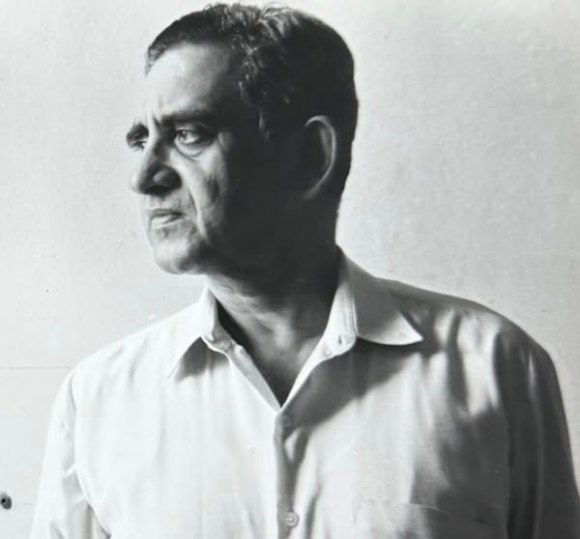

Ramakanta Rath is one of the most renowned modernist poets in the Odia literature. The quest for the mystical, the riddles of life and death, the inner solitude of individual selves, and subservience to material needs and carnal desires are among this philosopher-poet’s favourite themes. His poetry betrays a sense of pessimism along with counter-aesthetics, and he steadfastly refuses to put on the garb of a preacher of goodness and absolute beauty. His poetry is full of melancholy and laments the inevitability of death and the resultant feeling of futility. The poetic expressions found in his creations carry a distinct sign of symbolic annotations to spiritual and metaphysical contents of life. Often transcending beyond ordinary human capabilities, the poet reaches the higher territories of sharp intellectualism.

The contents have varied from a modernist interpretation of ancient Sanskrit literature protagonist Radha in the poem “Sri Radha” to the ever-present and enthralling death-consciousness espoused in “Saptama Ritu” (The Seventh Season). Some of his other major poetry collections include Kete Dinara (Of a Long ,Long Time), Aneka Kothari (Many Rooms), Sandigdha Mrigaya (Suspicious Hunting), Sachitra Andhara (Picturesque Darkness), and Sri Palataka (Mr. Escapist).

Ramakanta Rath was born in Cuttack, Orissa (India) on 13th December 1934 and passed way on 15th March 2025.

He obtained his MA in English Literature from Ravenshaw College, Orissa. He joined the Indian Administrative Service in 1957 but continued his writing career. He retired as Chief Secretary Orissa after holding several important posts in the Central Government such as Secretary to the Government of India. He received the Sahitya Akademi Award in 1977, Saraswati Samman in 1992, Bishuva Samman in 1990 and India’s 3rd highest civilian honour, the Padma Bhushan in 2006. He was the Vice President of the Sahitya Academy of India from 1993 to 1998 and the President of the Sahitya Akademi of India from 1998 to 2003, New Delhi. In February 2009 he was awarded a fellowship by the Central Sahitya Akademi.

These cantos have been excerpted from Ramakanta Rath’s own translation of his long Odiya poem, “Sri Radha”, by his son, Pinaki Rath.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International