By Farhanaz Rabbani

The grand images of a historic event flashed before her eyes, as 11-year-old Jui, flanked by her sisters, sat still in the dark hall of Gulistan Cinema Hall. There was a great buzz about the new Technicolor documentary on the coronation.

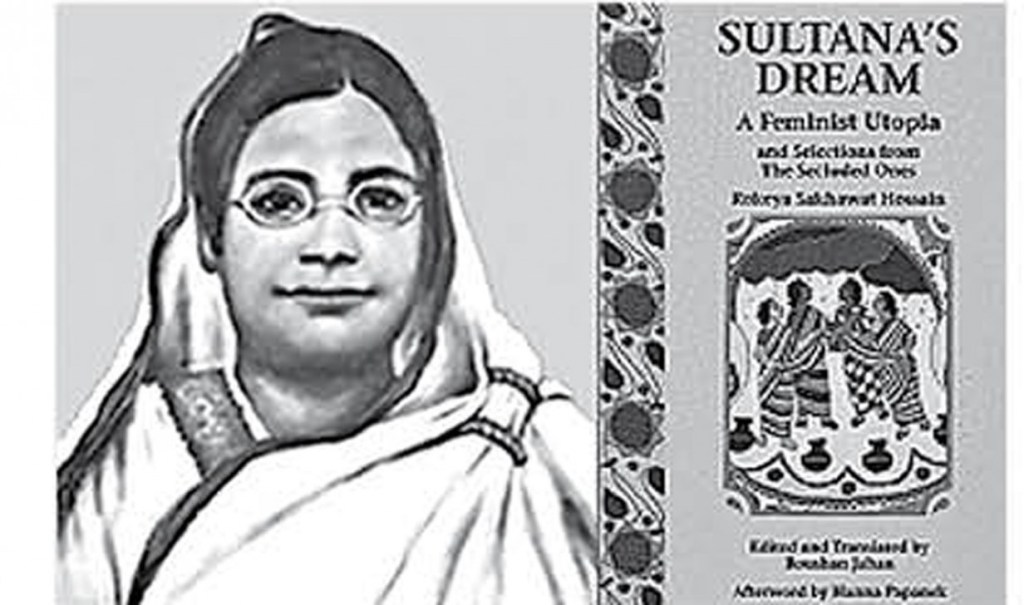

The week before she had heard her elder sisters, Ruby and Shelly trying to convince their mother to let them watch it at Gulistan. For an affluent wealthy Muslim family, allowing girls to watch movies outside was unheard of. But the matriarch of the family, Zubeida, was groomed in a different manner. Born of a renowned family in Munshiganj, she was educated at the Sakhawat Memorial Girl’s High School in the 1920s. Inspired by the values of the Bengali feminist writer and the founder of her school– Begum Rokeya Sakhawat Hossein, Zubeida was an avid reader and extremely aware of the social issues of her times. When she was married at the age of 14, her husband, a renowned physician, encouraged her to read at home.

Zubeida’s sons and daughters grew up reading the latest literary journals and novels written by legendary Bengali writers. Being the third daughter and the fourth among all the siblings, Jui was surrounded by casual conversations of the latest plays in town or the scintillating songs from the All India Radio. Her immediate elder sister Shelly was a huge fan of Dilip Kumar’s songs and was often seen pressing her right ear to the battery driven radio, swaying to the mellifluous melodies of S.D. Burman. But life was not all play in Zubeida’s home.

In the evenings, as soon as everyone completed their Maghrib prayers, the children had to study. Seven children had several different techniques of playing truant during this special time. The eldest son being an avid football player, would often stay away from home playing in tournaments for the Mohammedan team. The next child Ruby looked at life in a more serious manner. She sat on her table with the hurricane lamp illuminating her social studies book. But sometimes, Jui would often see books by Kamini Roy, or Ashutosh Mukherjee or Tagore hidden within the centrefold of the schoolbooks!

Once, their father had just returned from his medical chamber to catch Shelly pressing her right ear to the small battery driven radio intently listening to the latest Dilip Kumar song.

“Ruby’s Maa!” he exclaimed, “These girls will all get married to rickshawallas! All they do, every day, is to waste time. How will they ever pass their exams?”

While the veteran patriarch was fuming in rage, Ruby’s Maa, Zubeida, appeared to be totally undisturbed by his lamentations. She never worried about the future. With her deep faith in God, she took life one day at a time,

Ruby and Shelly were intently looking at the screen transporting themselves to Westminster Hall amid all the grandeur of the Coronation. The sultry voice of Laurence Olivier wafted through the Cinema Hall of Gulistan as images of a sparkling crown being placed on the elegantly styled head of Queen Elizabeth II mesmerized the audience.

Zubeida, in her usual quiet persuasive way, had convinced her husband to give them permission to watch the famed documentary on the coronation of the new Queen — Elizabeth II. Abu Chacha– their darowan 1 went to great lengths to get 5 rickshaws for the journey from Naya Paltan to Gulistan.

The ladies adorned themselves in their best attires. The older daughters gave special care to apply their homemade surma2 on their eyes. The younger ones were just too excited to have a day out with the ladies of the household. Zubeida wore a beautiful cream coloured saree with a black border, the dark kohl accentuating her dreamy eyes, and she had mouthful of paan that made her lips ruby red. With a splash of attar, the ladies wearing saris got on the rickshaws– all veiled meticulously — so that passersby would not see their faces.

Abu Chacha was relegated with the noble duty of guarding the ladies–perched on a sixth rickshaw keeping track of the ladies at the front. As soon as Zubeida and her daughters reached Gulistan Cinema Hall, Abu Chacha stood on guard at the front of the Hall. He was not interested in the coronation of a foreigner. His life was not affected by the wonders of the colonial rulers. His only loyalty was for Doctor Sahib — who saved his mother from her deathbed. He would dedicate his life to the service of Doctor Sahib’s family.

Jui was silent– perhaps a little overwhelmed by the discipline and formality of the whole affair. She wondered if she would ever break away from the confines of her home and see the world outside. She was always the quiet one. Since she was not as robust as her sisters, she was considered to be docile and shy. But the 11-year-old girl had a deep-rooted desire for breaking boundaries. The ornate gilded halls of Buckingham Palace flashed throughout the screen. Huge paintings framed in gold and the elegant procession of the Royal Guards clad in red and gold transported the audience to the glamour of the crowning of the new Queen of the United Kingdom. Jui, with her innate curiosity, watched the red canopy covering the Queen as she was anointed with holy oil. She had no idea about the significance of these actions. All she noticed was the splendour of a distant world – where women did not have to travel in covered rickshaws.

Queen Elizabeth’s calm but firm look seemed to send a message to this little girl thousands of miles away. As she sat on the cushioned seats of Gulistan Cinema, surrounded by her protective sisters, Jui suddenly felt her resolve strengthening. She wanted to know more and see more of the world. She dreamed of visiting the land of the Queen one day. She dreamed of breaking out of the confines of her home one day.

She would be the queen of her own destiny.

.

Farhanaz Rabbani loves to chronicle interesting stories and events that happen around her. She is an avid listener. Contact: fnazrs@gmail.com.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International