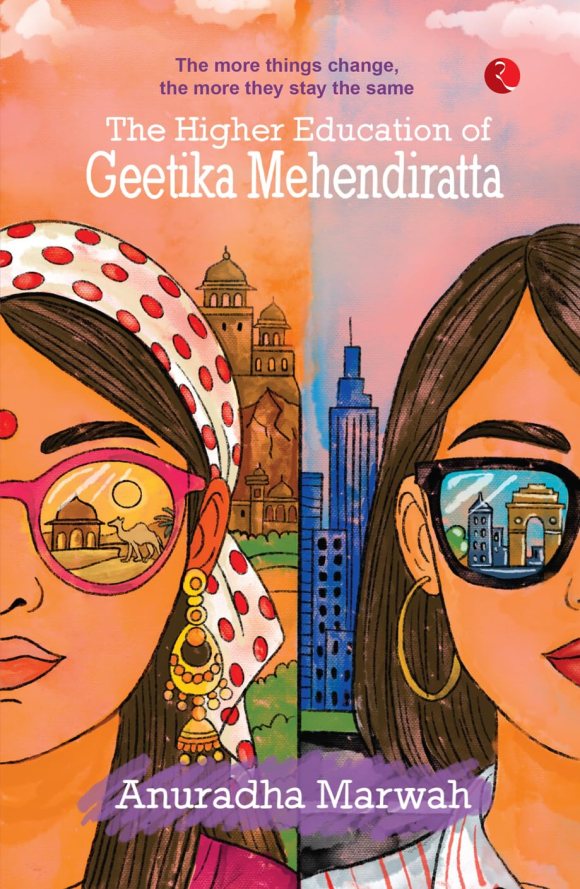

Title: The Higher Education of Geetika Mehendiratta

Author: Anuradha Marwah

Publisher: Rupa Publications

Boyfriend

There is communication because there is no communication, thundered the supervisor in a sudden spurt of lucidity.

Three dark heads bent obediently over the notebook to glean these pearls of wisdom.

‘When I say cat, you may think of a black cat, a white cat, a fat cat, a thin cat…’

I wondered where to put this in. I was going to write a dissertation on A House for Mr Biswas by V.S. Naipaul, I had decided last night. At what point should I bring in the feline? This brand new structuralist approach… For the past twenty minutes, this impressive lady from Sorbonne had only spoken about the difficulty in identifying cats. I had even drawn one in my notebook. Structuralism had spread far and wide, she had told us; it had reached Cornell, where a professor had simplified it at once for the simple non-European brain. Only Americans are capable of such simplifications, she had added laughingly.

Cornell, America… Vinita.

Vinita had changed so much. She now had a baby girl. She did all the household chores herself, she had told me. She had become plump. Her breasts had lost their upright quality; she had even started applying a lot of make-up—bright lipstick, mascara and eyeshadow.

She wouldn’t know about American universities though—that wasn’t the America she had gone to. She had gone to drudgery and loneliness… No servants to chat with all day long.

In Ratish’s house, there were servants… Lakshmi said Ratish was far too predictable. She said I was predictable too. That I would get married in a hotel, watched by a whole lot of people I didn’t know; that I would have two easy deliveries and be pleasantly miserable all my life. She even predicted I would get fat.

When I told her I wasn’t predictable and would make her sit up one day, she began singing ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun’.

Every discourse has a mediatory role as an instrument of change.

Who would mediate between my estranged parents and me?

Which discourse—the discourse of commitment or the discourse of tradition? Lakshmi or Ratish?

Ratish had come to Desertvadi to say that he loved me. Mummy had said it was absolutely dreadful the way I could never make up my mind about boys. She had cried. Andy had cried too; Papa was the only one who hadn’t. And then, suddenly, there had been a letter from the university saying I had cleared the written exams for the MPhil programme, would I appear for an interview?

I was where I wanted to be, for the first time in life, although the umbilical cord of parental expectations was yet to be cut… Ratish said he valued family and respected my parents, and that I should be gentle with them… Cruel to be kind, kind to the potential children in my womb. What if there weren’t any? What if I couldn’t have any? So much of our planning would go haywire, Ratish. I would have been cruel for nothing.

There would be nothing to do except cry or make a phone call to your office… No patter of little feet. What would I do with you then?

Tonight, we are going for a party, I will ask you then.

Words are either arbitrary or associational.

Is that a word, ‘associational’, or was it coined in Sorbonne this very summer? Lakshmi says it would be better to check the professor’s antecedents; perhaps she is not from Sorbonne at all.

Lakshmi looks down on our department anyway.

Economics people have this strange nose-in-the-air attitude towards languages. Our department was housed in the School of Languages, so everybody thought it was a Linguistics department… But we were doing literature, three of us. One was from Utkal University, Orissa; another from Ramakrishna Mission, Pondicherry; and I, from Rajasthan University.

I was disappointed that there was nobody from Lutyenabad in our course. All Lutyenabad students went to the Capital University because all the jobs were there. I had heard that there was a danger of never landing a job in Lutyenabad after doing an MPhil from Jana University.

So Andy, your curse may yet materialize—if I don’t have children and I don’t get a job. You had said as much, hadn’t you?

‘You will never be happy, Geetika, never… Don’t think you can find happiness by wrecking mine.’

But what could I do, Andy?

‘Geeti, my mother wants us to marry,’ you had said.

‘But Andy, my parents do not want me to marry yet.’

‘Look, the situation is getting very difficult for me. My parents are rather worried about the fact that your parents have not made any overtures to them.’

‘Why don’t you explain to them—’

‘I have done enough explaining. Your brother got married without even calling his parents for the wedding…’

‘What does Bhaiya have to do with this?’

‘Geeti, I can understand my parents… They didn’t question my decision to marry you. Surely, they are entitled to some sort of say in my affairs.’

‘I am not saying they are not…but Andy, what am I to do?’

You could never answer that one, could you, Andy? It just went on and on—your duty towards your parents, the obduracy of mine. I was tempted, sorely tempted, to just tell my parents that I was marrying you that very day but Ratish’s card saved me.

It came by the evening post the day you left Desertvadi after extracting a promise from me that I would speak to my parents. It was a lovely card; it said: ‘I can’t forget you, little one’.

It became easier to write that letter to you, dear Andy… It became easier to tell you, when you came running after receiving that letter, that it won’t work… But it wasn’t easy dealing with the lava of your frustrated anger as it burnt down my unsuspecting ears whenever I picked up the phone for months after that.

‘You bitch, you found somebody else at the Sportsaid, didn’t you? Don’t think you can ever be happy with him…’

Discourse becomes necessary because of the ambiguity inherent in the nature of language.

But I understood even what you didn’t say… I knew that I had wronged you, Andy. I did not cry as much as you did; I would have to make up for it. I had always appeased the gods by crying… This time, I slipped up…

About the Book: Desertvadi, Rajasthan, is a retirees’ paradise, but for a young girl like Geetika it is a claustrophobic trap. Academically gifted and sexually curious, she feels suffocated by small-town mediocrity and dreams of faraway lands and liberated lives – the kind that fill the pages of her beloved novels.

So, when an opportunity to study in the big, bustling Lutyenabad presents itself, Geetika leaps at it, eager to get away from her parents and the miasma of chronic boredom that envelops Desertvadi. Soon cosmopolitan life begins to feel like a snug fit especially when her new boyfriend, a famously fine catch, offers her the many luxuries of a conventional marriage.

But life in a metro impacts her in ways she never expected. Her aspirations inflate, her tastes evolve, and her ambitions solidify. As her boundaries expand uncontrollably and the daydreams she was escaping to inevitably shatter, Geetika is compelled to face some tough questions.

Published in 1993, The Higher Education of Geetika Mehendiratta was one of India’s earliest campus novels. Republished for a new generation, this is a bold and intimate coming-of-age tale – unafraid of its hunger and unashamed of its heat.

About the Author: Anuradha Marwah is a professor, playwright, and novelist. Her wide-ranging publications also include poems, essays, articles and reviews. Aunties of Vasant Kunj, her fourth novel was published in 2024 to immense acclaim. Anuradha lives in Vasant Kunj, surrounded by a community of trees and cats.

Click here to read the review of the novel

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International