Book Review By Rakhi Dalal

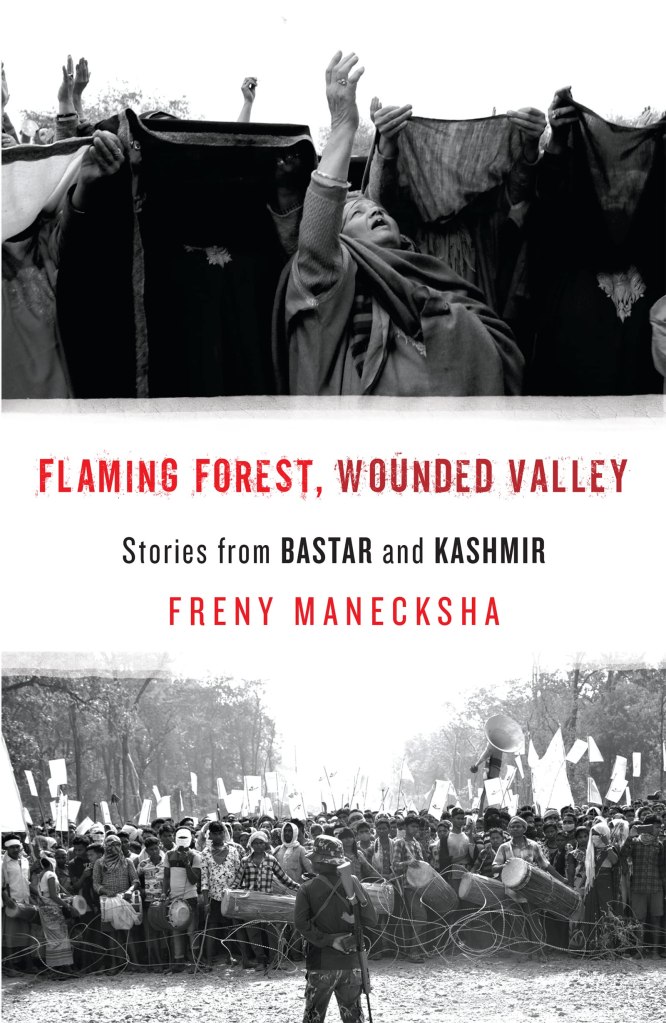

Title: Flaming Forest, Wounded Valley: Stories from Bastar and Kashmir

Author: Freny Manecksha

Publisher: Speaking Tiger Books

People who have never lived in or around conflict riddled zones, have a scant notion of how the politics of a nation impact survival in such places. In the name of curtailing extremism, the punitive measures adopted, achieve little more than turning daily living into a nightmare. How would one feel if the forces employed by a state, supposedly to safeguard the common people, barge into their homes unannounced at any time whether day or night and leave them terrified? Or, if a group of civilian people are fired at by the forces while sitting in their fields discussing as routine a thing as celebration of a festival?

In a country like India where the mainstream media turns a blind eye and sometimes help propagate a biased and false narrative, it takes courage of a few who, despite looming threats, try to bring in stories from such places, stories that tell of the oppression of common people both at the hands of extremists and the state.

Flaming Forest, Wounded Valley by Freny Manecksha is one such attempt towards bringing out truth from two militarized zones of the country – Bastar and Kashmir. Manecksha is an independent journalist from Mumbai. She has worked with Blitz, The Times of India, Mid-Day and Indian Express. She has travelled and written extensively from Kashmir and Chhattisgarh. She is the author of Behold, I Shine: Narratives of Kashmir’s Women and Children.

In documenting the accounts from these restive places, Manecksha draws parallels between the everyday struggle of people to live in their villages or homes, the distrust for the forces or police system because of the brutalities suffered, the hesitation to file reports because justice is seldom achieved, the state narratives which usually demonstrate scant regard for the people and their right to live with dignity, the impunity with which their lives and their bodies, especially those of women, are disregarded and desecrated.

In case of Kashmir, “the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) gives blanket immunity to the security forces against crimes like unlawful detentions, torture and custodial killings.” As a result, they can force enter a home at any time for a raid and search the entire house while deploying a member as a ‘human shield’. This makes the concept of home as a safe and inviolate space alien for the people because anything can happen at any time.

Neither home nor outside is safe. Whereas in Bastar, public institutions like schools become places for interrogation and torture, in troubled towns of Kashmir, the hospitals becomes places for identifying and arresting protestors. Shot with guns or pellet guns, the bodies become spaces trampled by coercion and ruined or silenced by violence. Their stories of suffering and pain find echo in a poet’s words:

“At an avant-garde cafe in uptown Pune the reserved tables celebrate a teenager’s birthday in cosmopolitan English My nearly dead phone flares up with a call from home My mother laments in frayed Kashmiri: I am happy you aren’t at home, two other boys Were shot dead today.”

The reports from these fractured lands are harrowing and forces one to delve into the motives and repercussions of State’s militarisation policy which, instead of maintaining peace, has brought unrest to people’s lives. Whether it is through Ikhwanis[1] in Kashmir or Salwa Judam[2]in Chhattisgarh, the state, irrespective of the Government at Centre, has tried to constrain people through violence. In the name of national interest, their lives have been dispossessed of the merit to normality. At stake as ‘collateral damage’, a term used by state or forces as matter of fact, has just not been their lives but also the dignity in death. The struggle, whether of the Adivasis of Bastar or of people from Kashmir, has been to reclaim their everyday life, their land and their homes.

These stories, however, are also those of resilience. The book celebrates the idea that even in the face of tortures and abuse, collective grief transforms into collective sharing which make people stand together and claim their rights to live. Manecksha writes with empathy and tenderness. Her reportage reflects the efforts that are put in collecting these narratives. It is a book as critical as it is relevant to our times.

[1] Religious Militia

[2] Militia employed to crack down on counterinsurgents

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ .

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

Click here to access the first Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles