Book Review by Rakhi Dalal

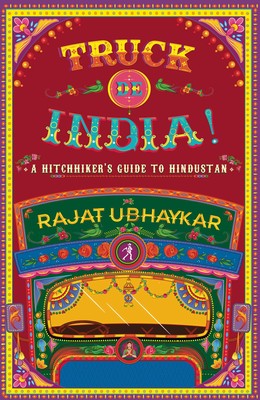

Title: Truck De India

Author: Rajat Ubhaykar

Publisher: Simon and Schuster, India, 2019

“Gaddi jaandi ae chhalanga mardi

(The truck goes jumping)

Mainu yaad aaye mere yaar di”

(I remember my beloved)

The one image that I have always associated with the thought of truck/ goods carrier on Indian roads is a boisterous Punjabi driver driving the truck in abandon while singing this song full throttle. Part of the reason lies in my spending my early childhood years in Punjab and part in being enamoured by the bitter sweet song which is as much about love as it is about lamenting the distance between lovers.

But apart from this sweet image, one other image that has been deeply ingrained in my mind about these trucks is that of a formidable giant body on wheels which must never ever be overtaken on a highway.

This was one of the first lessons I was given while learning to drive – “Don’t ever overtake a moving truck or a bus, especially on Haryana Roadways.” So while I have adhered to this rule most of my life, sometimes I have indulged in the guilty pleasure of overtaking the giant on a highway, more specifically whenever I found it trudging painfully slow. It generated a sense of exhilaration when I beat the king of the highway on its own territory.

But other than this, the sight of a truck never evoked much contemplation. That was not until I came across Truck De India.

Really, I thought? A book on trucks? WOW.

And then I read the subtitle – A hitchhiker’s guide to Hindustan

In the prologue of the book, the author narrates the incident which kind of seeded the idea of discovering the country through road:

“Staring outside the window on that trip, the wind tousling my unruly hair, I remember being struck by a sort of epiphany, that India is bigger than the boundaries of my imagination, or anyone’s, for that matter. You didn’t have to go the scale of the cosmos to imagine something vast – India was enough.”

That the author, Rajat Ubhaykar, chose trucks to hitchhike to undertake the journey was at first kind of bewildering to think. But then as I read on, I realised what better way to discover a country if not through the eyes of one of the most vulnerable yet surprisingly one of the most underrated and suspected class in the workforce of the unorganised sector which forms the backbone of logistics across the country.

Another reason might be the mysterious air that hovers around the sight of a truck on a highway. It seems to be destined for discovering vistas unknown to commoners like us and so the experience of its riders may seem much richer than that gained through journeys undertaken by conventional means.

Ubhaykar started the journey from Mumbai, moving all the way upto Kashmir and then Far East to Nagaland before finally reaching Kanyakumari in the South. A journey across the country hitchhiking thus with truck drivers and their helpers, gave him a first-hand experience of the many tribulations and dangers they face while transferring goods for people like us — the goods we eventually consume unthinkingly.

What I found immensely likeable about his hitchhiking with truck drivers is that he entered their world only when taken kindly in. Throughout, he maintained a respectful distance while asking questions about their lives, their experiences. He found that apart from paying “taxes” on road to braving harsh weathers, the threat of insurgents or evading highway robbers, the drivers also spent long periods away from family only to save a couple of thousands more. But none of the problems that they faced made them hostile as they conversed about these with a total stranger. In fact, as opposed to the commonly held notion, he found most of them very friendly and warm.

“Aap humare mehmaan hain” (you are our guest). How else can one define the gesture of the driver paying for a stranger’s meal where a single penny mattered to him? Or sharing the already cramped space for two to sleep with someone they had barely met? What held them together apart from the commonality of being part of the same journey from one destination to the next? Or was it the inherent human desire for the need to be understood, respected and treated kindly by fellow beings? In the journey of life each of us choose a path, most suitable circumstantially, and so, a comparison materialistically is not only naïve but also degrading.

While on his journey to initially discover the unseen India, Ubhaykar found what really mattered were the transits which characterise life. He has penned his experience to showcase what happens in the lives of the truckers who spend most of their lives behind wheels — away from their loved ones — to ferry goods and materials which not only run our country’s economy but also bring comfort to the lives of millions of strangers.

It is fascinating to enter Ubhayakar’s world of truckers in India who live with the uncertainties of highways and circumstances to earn their livelihoods. Now, with this book by your side, are you ready to embark on the ride?

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ . She lives with her husband and a teenage son, who being sports lovers themselves are yet, after all these years, left surprised each time a book finds its way to their home.