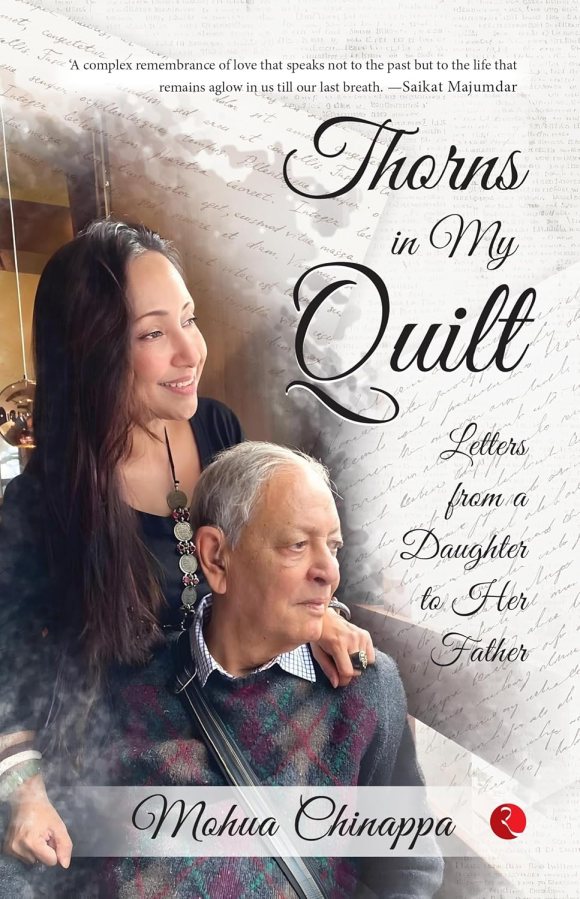

Book Review by Rakhi Dalal

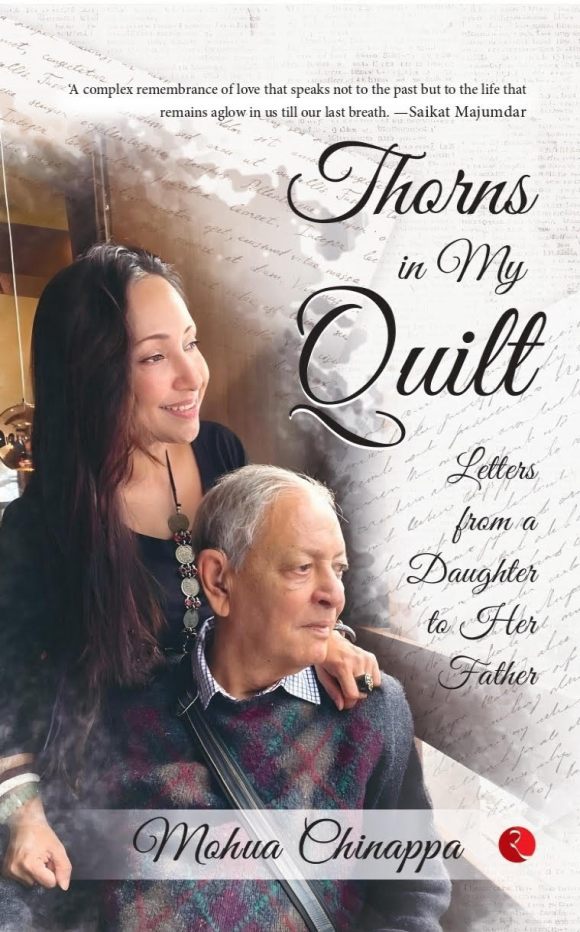

Title: Thorns in My Quilt: Letters from a Daughter to her Father

Author: Mohua Chinappa

Publisher: Rupa Publications

Mohua Chinappa’s Thorns in My Quilt: Letters from a Daughter to Her Father is a quiet and visceral exploration of memory, grief, and the often-fraught space between love and silence. Drafted in the form of a collection of letters to her late father, the book is less about resolution than about reckoning – more an attempt to articulate what remained unsaid while he was alive. Chinappa, through this profoundly personal lens, not only offers a portrait of a relationship but also a reflection on absence, yearning, and the emotional inheritance that we all carry forward sometimes.

Mohua Chinappa is an author, a columnist, a renowned podcaster in India, a TEDx speaker, a former journalist and a corporate communications specialist. Her other initiative—NARI: The Homemakers Community—provides a platform for homemakers to voice their everyday challenges.

The letters in this book, seamlessly weave together fragments of childhood and adulthood, moving fluidly between time and place. One moment, Manu the daughter, beckons the warmth of her early years in Shillong — vanilla flavoured butter cookies and the hush of rain-soaked afternoons, then the shelter of a harsingar[1] tree in their government house in Delhi, while in the next, she confronts the frailty of her marriage, the weight of her Baba’s illness, or the sting of words that sometimes remained unsaid. The form of writing echoes the workings of memory. Not linear, but recursive, continually turning back to moments that remain unresolved. Each letter seems like an appliqué sewn into the fabric of remembrance, creating a quilt with seams held together by both tenderness and pain.

At the centre of the book is the paradoxical figure of her Baba, portrayed with candour as a man who is loving yet aloof, erudite yet impractical and admired yet sometimes resented. Manu longs for his approval but also grapples with the ways his criticism and aloofness diminishes her. The letters vacillate from affection to accusation and from gratitude to grievance. In the acceptance of these contradictions, there seems a resistance to recall the memory of a father in an idealised tone. Instead, Chinappa manages to present a figure whose complexity remains inseparable from her own. The portrait revealed, thus, appears all the more moving.

The narrative also reverberates with a strong theme of displacement. The family’s history of migration, the shifts between Shillong, Delhi, and Bengaluru, create a sense of being both rooted and uprooted at once. Places do not act merely as backdrops but are living repositories of memory, holding within them the sweetness of belonging and the ache of estrangement. This sense of dislocation extends inward in the narrative. Chinappa captures not only her alienation from her father but also the broader struggle of carving an identity in a world shaped by expectation and silence.

The language of the narrative is lucid, and doesn’t tip into ornamentation. Everyday details—trees, rain, food, household objects—become charged with metaphorical weight, carrying emotional resonance far beyond their surface. The letters are suffused with sensory detail, grounding the reader in the textures of lived experience while also opening space for reflection. The writing exercises restraint. Even at its most poignant, it doesn’t spill into melodrama.

The emotional honesty of the book is equally striking. Manu does not shy away from confessing anger or disappointment; nor does she smooth over her father’s failings in the name of filial devotion. She admits to her vulnerabilities—the yearning for acceptance, the bitterness of abandonment, the pain of reinvention when life’s foundations collapse. These allow the readers to relate with the story. Though the particulars may differ, but the longing for parental approval, the hurt of unspoken words, and the struggle to reconcile love with resentment are universal.

However, some constraints in the narrative cannot be overlooked. The epistolary form, while effective in evoking intimacy, also narrows the perspective. Baba appears only through Manu’s voice, his presence mediated entirely by her memories and emotions. At some places, the narrative shifts abruptly, from addressing second person (father) to third which makes the reading a bit disconcerting. At times, the absence of other perspectives leaves the figure of father more shadow than substance, defined by what he was to her rather than who he was in himself. The letters also occasionally return to the same emotional terrain, circling around familiar grievances and sorrows. While this mirrors the looping nature of grief, the repetition creates a sense of exhaustion.

These reservations, however, do not diminish the book’s overall appeal. Its power lies not in neatness but in its willingness to dwell in ambiguity. It does not offer easy closure, nor does it attempt to tidy grief into a narrative of redemption. Instead, it embraces complexity, acknowledging that love is rarely unblemished, that absence can wound as much as presence, and that the act of writing itself can become a form of survival.

Thorns in My Quilt resonates because it is both deeply particular and quietly universal. While grounded in Chinappa’s personal history, it speaks to the wider human experience of fractured relationships, cultural displacement, and the longing to be heard. In cataloguing both the thorns and the blossoms of her bond with her Baba, Chinappa creates a testament that is as much about resilience as it is about grief.

[1] harsingar: Night Jasmine

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ .

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International