Book Review by Rakhi Dalal

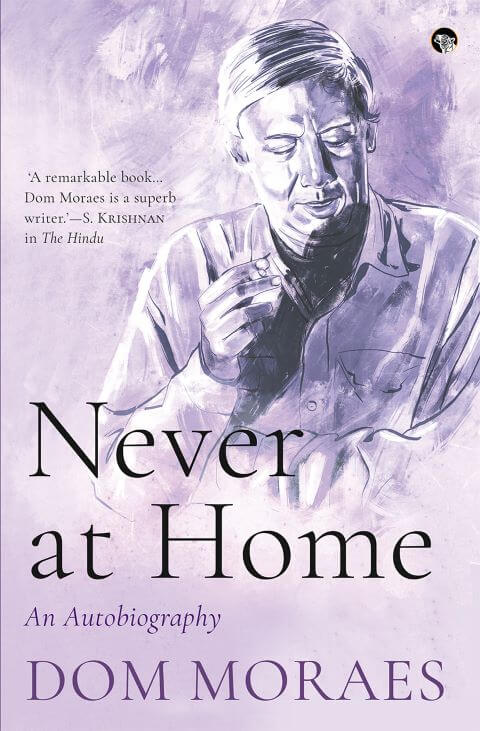

Title: Never at Home

Author: Dom Moraes

Publisher: Speaking Tiger, 2020

Never at Home is the third memoir in the trilogy of memoirs written by Dom Moraes. The others being Gone Away (1960) and My Son’s Father (1968). This volume was first published by Penguin India in 1992. Here the author writes about his life from 1960 onwards.

The first chapter is a brief account of the phase of his life after winning the prestigious Hawthornden prize at the age of twenty. By the time he turned twenty two, Moraes already had two poetry collections and a memoir to his name. In order to earn a livelihood, he then started writing features and reviews for newspapers. In 1965, he brought out his third poetry collection John Nobody. After James Cameron impelled him to take up journalism, Moraes started travelling and for the next seventeen years he couldn’t write poetry. For someone, who from his childhood knew that he wanted to be a poet and to live in England, he spent a considerable period of his life in transit without writing any substantial poetry. Never at Home chronicles those years he was engaged in navigating the world to collect stories and interviews.

This volume is the third and final in his collective memoirs – A Variety of Absences, which take its name from the poem Absences written by him after a long hiatus from poetic fervour. The book focuses more on Moraes’ professional life as compared to his personal life taken up in his second memoir so that its prose is not as poetic or intense as in My Son’s Father but nevertheless, it is a notable piece of literary writing. It may also be deemed as a historical archive because it records some very important and interesting snippets and observations from the political world he traversed and eminent leaders he met.

The critical success of Gone Away, his first memoir, brought him writing assignments which included scriptwriting for a documentary on India. As a journalist, he covered Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem and wars in Algeria and Israel. In his mind he had always been an English poet in England and had no idea of the tribulations other immigrants faced. A BBC documentary commissioned to him made him look at the living conditions of Asian immigrants, specifically from India and Pakistan. This documentary brought him closer to the reality of being an outsider in a foreign country.

While writing articles for The New York Times Sunday Magazine, Daily Telegraph, Nova and many others magazines, he met and interviewed many distinguished personalities and important world leaders but perhaps none left as deep an impression upon him as Indira Gandhi, whose biography he was later to write. The liberation of East Pakistan, now Bangladesh, had made her a star in the eyes of its natives who were till then hostile to Indians. Moraes writes at length about his meetings with her, about her charismatic personality, political astuteness and her almost invincible demeanor.

His descriptions of the journalistic assignments, which took him across many countries and gave him the opportunity to bring out stories to the world, are finely detailed. His keen eye presents a balanced perspective on the stories he covered, never going too far and never delivering too less. His most important works included a story on political prisoners in Buru and on the tribal people in Dani in Indonesia, the titles of the articles being ‘The Prisoners of Buru,’ and ‘The People Time Forgot’. His Buru piece evoked a violent response in Indonesia. Moraes was banned from entering the country again. But this piece was the first one to come out from the place and the issue was picked up by some human rights organisations leading to a release of seven thousand from the imprisoned ten thousand people. This, if anything, is a proof of the important voice he had become in journalism.

Although, Moraes’ work kept him busy in the world but he could somehow never get rid of the images of his traumatised childhood. As in the case of his second memoir,here also he writes considerably about his fear of confronting his mother. The accounts of his meetings with her are laced with the anguish and anxiety he had experienced in her presence always. Except his mother, all the other women in his life are only addressed in passing. He never dwells much upon his relationship with either his second wife, Judith, mother of their son Francis, or with his third wife, Leela Naidu. In comparison, his association with his friends and work colleagues occupy more space in this memoir. His regret for not becoming the father he thought he was when he wrote My Son’s Father comes perhaps due to his inability to express what he felt before others, including his family.

Moraes picked up journalism as a vocation to earn a living but it brought him closer to real life. His punctuated visits to India, whether to write on Naxalbari movement, to meet Indira Gandhi, King of Sikkim or to explore Rajasthan, led to an increased understanding of the country of his birth. Nonetheless, he was never at home in India or in the country he had adopted as a youngster.

The disquiet that marked his life is perhaps most poignantly conveyed in this line towards the end:

“I am waiting to be at home; where, I don’t know yet.”

As he settled in the country of his birth, after all the travelling, his muse did eventually return to him. The various absences – of a mother, a father, his friends from the youth or his son — at different times in his life and their memories, continued to haunt him. Yet this memoir ends with a hopeful note. In author’s words, “the best thing to do is to preserve some form of balance on the constantly moving ground tectonic plates of this planet.”

.

Rakhi Dalal is an educator by profession. When not working, she can usually be found reading books or writing about reading them. She writes at https://rakhidalal.blogspot.com/ . She lives with her husband and a teenage son, who being sports lovers themselves are yet, after all these years, left surprised each time a book finds its way to their home.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.