Book Review by Basudhara Roy

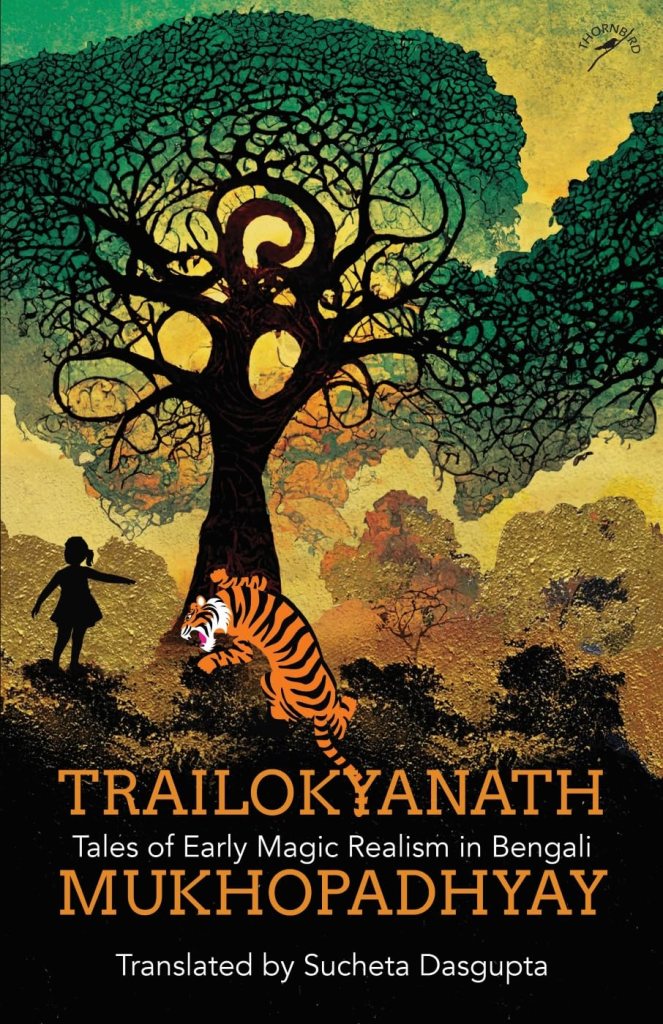

Title: Tales of Early Magic Realism in Bengali

Author: Trailokyanath Mukhopadhyay

Translator: Sucheta Dasgupta

Publisher: Niyogi Books

A good translation is a sorcery of desire, determination, and language. It opens a portal into not just another culture, reminding us of the texts, subtexts, contexts and conned texts richly underlying words but involves an admission into a whole new world that the reader would have missed altogether had it not been for the sincere striving of a visionary translator.

For, indeed, all translation is built around a vision that extends beyond that of giving life to a work in another language. There has to be a rationale as to why this reincarnation should, at all, be necessary or worthwhile, a logic as to how this can be effectively worked out in the asymmetrical arena of languages, and a dream as to what can be accomplished through this.

In Sucheta Dasgupta’s case, the translation of Trailokyanath Mukhopadhyay’s Tales of Early Magic Realism in Bengali stems from a desire to introduce readers of English to the wide, vibrant, unusual and remarkably fabulist world of the author as a pioneering attempt in the field of global speculative fiction.

Speculative fiction as a genre, is an umbrella term that stands for all modes of writing that depart from realism. It includes myth, fable, fantasy, surrealism, supernaturalism, magical realism, science fiction, and more. Being a speculative fiction writer herself, Dasgupta finds in Trailokyanath’s world an interesting attempt at “creating these genres and bending them in Bengali, in nineteenth-century United Bengal” which, to her, was a revelation of sorts.

Her intention to bring Trailokyanath Mukhopadhyay to the attention of a wider international audience has helped to add to our understanding of the rich and diverse society of nineteenth-century Bengal and its conflicting intellectual inheritance. This translation, in vital ways, also does service to Bengali literature in which Trailokyanath’s reputation has remained eclipsed and which, following Tagore’s estimation, has mostly looked upon him as a children’s writer.

A mere glance, however, at the six interesting translations in Tales of Early Magic Realism in Bengali will clarify that they are far from yarns meant for children. Driven by a clear vision to make sense of their times by negotiating between two distinct epistemologies – the native and the colonial, these are essentially narratives of ideas that speak to the confused public conscience of the age.

The tales, in question, are ‘Lullu’, ‘Treks of Kankabaty’, ‘Rostam and Bhanumati’, ‘The Alchemist’, ‘The Legend of Raikou’ and ‘When Vidyadhari Lost Her Appetite’. These are, properly speaking, ‘tales’ that stem from and echo a fecund oral tradition of storytelling and answer to no formal conceptions of the short story genre. They are indiscriminate with regards to length, plausibility, fineness, and intention and except for the last story which exemplifies a certain tightness of plot and effect, these tales are characterised by a clumsy looseness which marks oral forms.

Rich in description and sensory detail, each of these stories has its own distinct style and flavour. While ‘Lullu’ and ‘Treks of Kankabaty’ are pure fantasy, ‘Rostam and Bhanumati’ and ‘The Legend of Raikou’ weld elements from myth and folklore. ‘The Alchemist’ attempts to combine moral treatise and scientific history together while ‘When Vidyadhari Lost Her Appetite’ sticks to realism, emerging as the most well-told tale in the collection terms of both craft and cultural representation.

How far it is justified to call these six narratives ‘tales of early magic realism’ remains a question well-raised in the ‘Foreword’ to the book by Anil Menon where he points out that the bringing together of realism and fantasy sans the socio-political context of the twentieth century seems inadequate. “What we can say is that there is a magic realist reading of such-and-such work. The classification refers to the relationship between the reader and text, and not to some essence in the text itself.”

Trailokyanath’s world, whether realist or fabulist, is the world of a robust, liberal, discerning intellectual who is well aware of the various currents and counter-currents of native and colonial reflection of his times, all of which he adroitly conjures in his fiction to offer readers sumptuous food for thought. While these tales might want in artistry and unity of effect, they revel in ideas and the multiplicity of points of view which offer readers today a very faithful portrait of nineteenth-century Bengal and the intellectual debates that actively ranged on issues such as religion, widowhood, sati, women’s education, fashion, the codes of marriage and remarriage, caste, family, and economy.

Dasgupta makes sincere efforts to offer as honest a translation as possible, (“I fully intend my work to be the ‘same text in a different language’ and not a transcreation”, she points out in her ‘Translator’s Note’.) retaining native words where there are not acceptable substitutes and offering a well-researched and nuanced glossary at the end of each tale to point out Bengali meanings and usages. The prose style of the book, following the original, tends to be ornate at places but the humour and satire that gives sinewy form to these tales is unmissable.

In ‘Lullu’, for instance, Aameer insists that the only qualification for an editor of a newspaper is the ability to curse and his purpose in choosing to appoint a ghost as editor was that “…all the curse words known to man have been spent or gone stale from overuse. From now on, I will serve ghostly abuse to the masses of this country. I will make a lot of money, I am sure of it.” In our own times, the experience of sensational headlines and of fake news, and the sight of bickering spokespersons and screaming anchors in newsrooms makes us smile at Trailokyanath’s foresight.

In ‘Treks of Kankabaty’ which attempts to be a Bengali adaptation of Lewis Caroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865), a mosquito informs the protagonist that the true purpose for which humans have been created is so that mosquitoes “can take a drink of their blood”. “All mosquitoes,” states Raktabaty “know that humans have brains, but no intelligence. The foolish amongst us are called humans in the pejorative sense.”

A comic geographic, cosmic and karmic purpose for the traditional religious prohibition on travel for Indians emerges in this tale:

“India is surrounded by the black waters on three sides while on the other, there are gargantuan mountain ranges. Just as animals are kept inside a paddock, so, too, we had kept Indians enclosed by the means of these natural fences. By staying in India, Indians so far had remained at our service and humbly donated their blood for the purpose of our nourishment. Not so any longer. Today, some of them are waging attempts to cross the high seas and conquer the mountains. That if they behave thus and deprive us of their blood, they commit a great sin is common knowledge.”

Again, on hearing that “the British have banned the custom of sahamaran[1]”, the monster Nakeshwari says:

“Well, the British did ban the custom, but do you know what the young and educated Bengali men believe today? They believe in restarting old customs in the name of Indian pride. They have gone stir-crazy in the name of throwing their grief-stricken mothers and sisters into the burning fire. And we, monsters, heartily support them in their mission.”

In ‘When Vidyadhari Lost Her Appetite’, humour aligns with stark realism in this argument between two maids:

“One day, Rosy addressed Vidyadhari, ‘Have you lost your judgement? Just this morning, you went to the confectioner’s shop and bought Sandesh for the master. Before serving it to him, you let the brahmin lick at it twice and then you, yourself, gave it ten good licks. When did you say to me, “Rosy, why don’t you, too, give it a couple of licks?” If one attains something, one’s duty is to share it with others.”

Common to all these tales is the empowering of the marginalised, a challenge to status quo, and a sustained intention to speak the truth for empowerment. In that sense, these narratives are all anti-authoritarian and disrupt various forms of hegemony to establish a vision of life that is swift, changing, capable of responding to oppression with wit, and where the spoken word has sacral value. That is why in ‘Lullu’, Aamir’s thoughtless remark ‘Le Lullu’ to frighten his wife actually summons a ghost called Lullu who spirits her away. Similarly, in ‘Treks of Kankabaty’, the moment Kankabaty’s father says, “…if a tiger appears in this very moment and asks for Kankabaty’s hand, I shall give it to him”, a roar is heard and a tiger appears seeking her hand in marriage.

Language, in its diverse potential, becomes an important thematic link in these tales and in this immensely polyphonic text that unleashes a host of voices, human and non-human, to capture a reality that operates on multiple axes and can be best appreciated through the third eye of the imagination.

.

[1] Dying together — A wife(or Sati) was burnt in the funeral pyre of her husband. This custom was banned in India by the British in 1829 and continues banned.

Basudhara Roy teaches English at Karim City College affiliated to Kolhan University, Chaibasa. Author of three collections of poems, her latest work has been featured in EPW, The Pine Cone Review, Live Wire, Lucy Writers Platform, Setu and The Aleph Review among others.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International