Book Review by Madhuri Kankipati

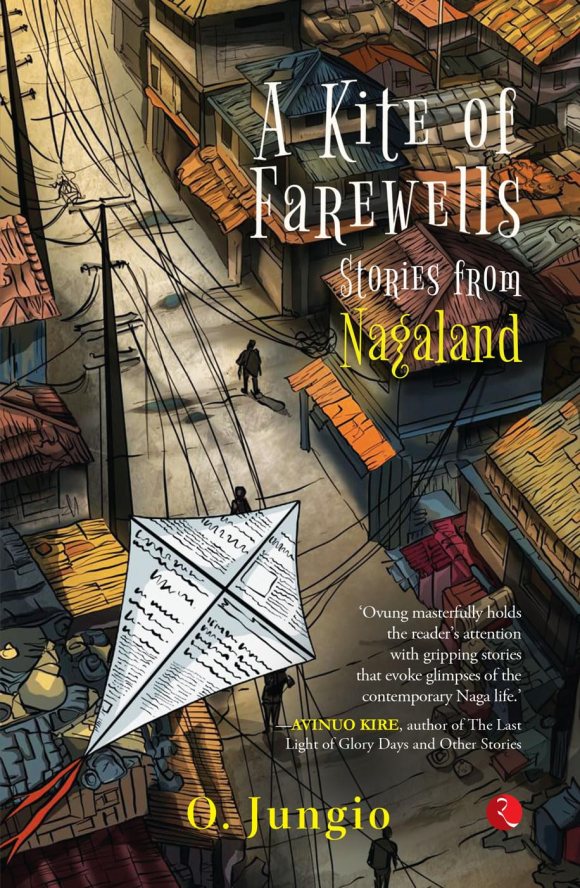

Title: The Kite of Farewells: Stories from Nagaland

Author: O’Jungio

Publisher: Rupa Publications

O. Jungio’s The Kite of Farewells: Stories from Nagaland is a collection of short stories of longing and grief set in contemporary Nagaland. The author is a tribal studies scholar, and cultural historian whose research and essays focus on oral traditions, folklore, and socio-cultural changes among Naga communities. In the book’s preface, he writes, “The objects—mute spectators to human sorrow—become the vessels of collective grief, the repositories of the most intimate of the farewells”. And every story in this collection does explore of longings of different kinds followed by farewells.

The first story, ‘Fire’, begins with a man driving in a downpour. He forgot to carry the food packed by his Ayo’s(mother’s). Like many others she believes hotels are “vectors for every ungodly disease in the world masquerading as something palatable.” What follows is at night he ends up in a strange village for food and shelter; where it seems like the lines between the living and the dead are blurred. The narrator chances upon a man who serves him raw food. He notes, “perhaps by way of some idiosyncratic tradition, this village served raw food on this particular day of the great harvest” and starts a fire to cook himself only to be spooked out by the man. Despite his longing for food, he has to make an escape.

In ‘The Encyclopaedia of a Salesman’, a young man selling encyclopaedias meets a retired government official. Initially, the narrator is cautious about why a man so steeped in command would be interested in something as democratic as encyclopedias. He reflects: “With a career of bossing around subordinates, were more inclined to be loud in their admission of suspicion and disinterest in things that challenged and subverted their sphere of command. What annoyed such men more was the vague possibility that for once in their life they would be hoodwinked by a lesser man like me. It would amount to an abominable upset of social order.” This single observation is enough to collapse multiple distances of age, profession, class. The salesman’s mind, seasoned by years of observation, becomes its own encyclopedia. Just when the disparity gets real, Jungio reminds us of a harder truth: that conversations end.

Jungio tries play on the longing for nostalgic memories in ‘Scoreboard’, highlighting an exchange about keeping a manual scoreboard for FIFA world cup 2017; the son arguing “you can get match summaries and stats from google” for the father to brush it off with “it has been a tradition for me”. The whole act of hanging a whiteboard with teams playing and the predictions along with their scores stands out as a cherished activity for the season. When tragedy strikes, that brief exchange transitions itself into a way of longing, in the practices we all hold on to after the passing of loved ones.

It is not just about the personal objects of longing, but also the social objects, or feeling like a forgotten object that has stood still in time. In the story ‘Showroom’, we meet a middle-aged man, who has always “shopped cheap and done so unapologetically,” visits a new mall in town after much contemplation, only to find himself embarrassed when he misunderstands the mall purchase policy. The story is tinged with humour.

In ‘Sacred Crow’ the concept of ‘Echu Li’ is introduced to the reader and the protagonist at the same time as “a world not different from ours. It is a transient stop for the dead before they move on to the Great Home, where they all would become noble spirits, formless like the wind” — which presents itself as an acceptance of loss. The protagonist awaits the black crow, building curiosity only to close on a note that better fits the tales passed around orally in rural Nagaland.

The final story, ‘The Newspaper Kite’, features four rowdy boys who “create” trouble for their neighbours with their games, their little understanding of familial financial struggles and a bond they both form with a man in his sixties. They lovingly call ‘Amotsu’ when he kindly returns them their newspaper kite in a new frame the boys “dropped” in his garden. The boys find joy in a paper boat because “Lofty ideas are, to an extent, a luxury when the means to materialise it are limited or absent. When you are poor, you train your mind to dream on a budget, and some days, you surprise yourself by getting so much out of so little.” When the boys find about the sudden demise of the Amotsu, they remember his words, “There is always a next day,” with the awareness that the coming days would be without Amotsu. It is in the memory of “that thread trick Amotsu used to do” while flying kites, the boys stay connected to the person who left this world.

O. Jungio does a balancing act between inherited lore and the present. He subtly hints at that it is the lore that differs from landscape but not the emotions or beliefs. Regardless of the objects that offer solace, people connect with the commonality of emotions.

.

Madhuri Kankipati is a reader, writer, and translator with too many hobbies and refuses to pick just one. She was raised to follow instructions, but the real world doesn’t work that way, she just stares at her problems. You can find her on instagram @withlovemadhuu

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Amazon International

One reply on “The Kite of Farewells”

Such an insightful review, makes me want to pick up the title!

LikeLiked by 1 person