Narratives and photographs by Prithvijeet Sinha

Talking about Vilayati Bagh as being an isolated cousin among the many gardens and monuments of Lucknow would be feasible given its elusive nature. I say elusive because it is nestled in the lush environs of the cantonment area and forested canopy that lies ahead of Dilkusha Palace which is one of the city’s many frequently visited wonders. Within this canopy lies Vilayati Bagh, “Vilayati”(foreign) referring in no small terms to not only a colonial past but also the stark fact that it is home to three tombs of erstwhile British officers who perished in the high noons of 1857’s First War of Independence. It was only a year ago that I, myself, had the opportunity to go there for the very first time. But that March morning changed everything. I have been there twice already to revel in its tranquility.

Its history is quite like other gardens and leisure spots of Awadh. It was built in the earlier parts of 19th Century by Ghazi Ud-Din Haider[1], the Nawab of Awadh, as a gift for his beloved European consort. During the revolt of 1857, it fell prey to shellings and other bombardments. But like most of Lucknow’s quintessential monuments, the spirit of renaissance did not elude it for long. In the present day, it is still tucked away in its quiet corner, slumbering and awakening for discerning eyes (and minds) who go there to capture crucial echoes of its unique identity.

Flanked by the Gomti close by and a cemetery in the middle of a spacious compound, the property begins its enchanting passage as one takes a straight drive (or walk) from Dilkusha Palace, approaches Kendriya Vidyalaya and then continues to move ahead to encounter a railway crossing, opposite which lies the cantonment granary, quarters and the grand and haunting Bibiapur Kothi. Taking a left turn from that location brings one to the verdure of old, huge trees, a moderately spacious road and pleasant sounds of cicadas and birds. In this pithy journey to Vilayati Bagh, the feeling of time-traveling to a gracious era of architectural elegance comes into sight the moment we reach its immediate premises. A beautiful Sufi dargah bathed in impressive green lies on the left and a few moderate homes of those who probably maintain this compound meet us.

Then the real journey begins. A sophisticated sense of the building blocks of this elusive garden are elucidated by its brown- yellow, almost auburn walls. The lakhauri[2] paint and plaster give it luster on a sunny day. These ramparts retain their history of age, war and past reckonings. Yet it’s the sun that designs their colour schemes in the most sublime shades. Archeological Survey of India has restored its lost glory in recent years and the result is there for all to see.

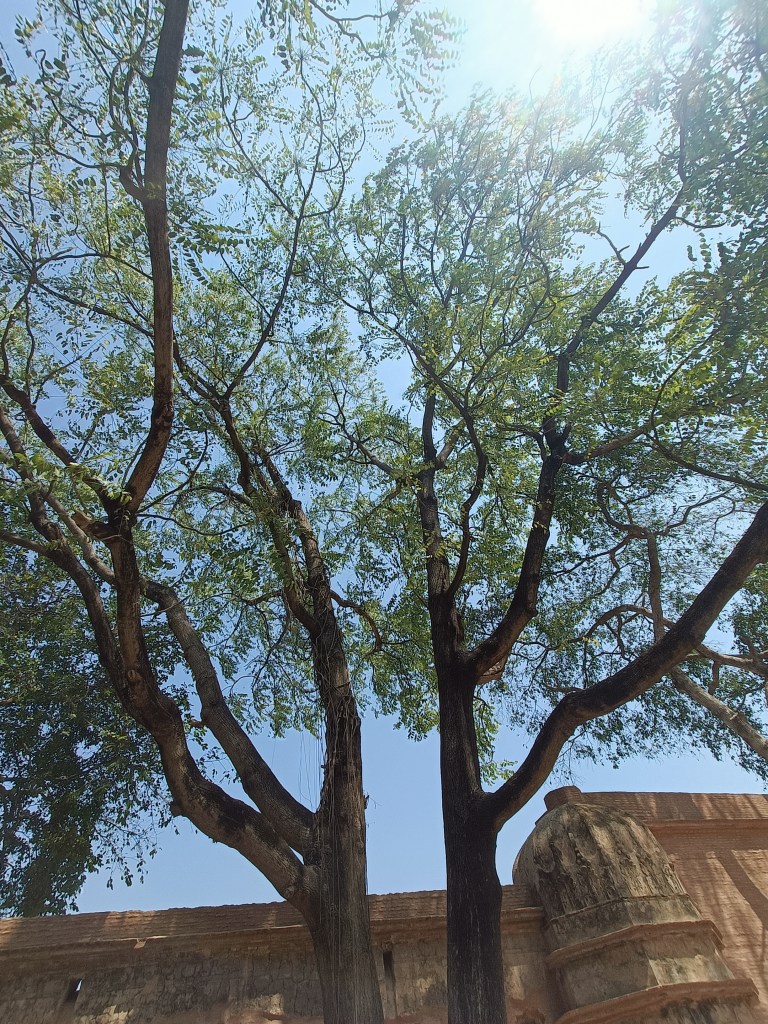

The boundary walls have a sturdy presence and are enclosed by arrow-shaped iron structures painted in pleasant brown. As one explores the interiors of the garden compound, little monoliths, corrugated outer flanks that look like barracks emerge, the exposed bricks red and pink in their sublimity of skin tones. A Y-shaped drain also flanks them. There is an aura of extraordinary peace all around. This isn’t meant to be a tourist spot. This is the one for aesthetes and true aficionados of history. The mind wanders and is arrested by trees whose branches are shaped like pitchforks.

A dargah (miniature Sufi shrine) greets one at the outer end of the compound while a majestic gulmohar tree seems to appear like a tall fellow wearing red scarves. Arches and domes subsist in this sturdy network of walls.

The saga of Vilayati Bagh is one of beauty but the starkness of its melancholy is evident in the cemeteries that lie in a little distance from the main gateway. They belong to fallen English soldiers Henry P. Garvey, Captain W. Helley Hutchinson and Sergeant S. Newman. These tombs are made in the image of a wide basin, crypts depicting that no one side can win or lose a war. Everybody has formidable stakes, and the dead don’t preach the gospel of victory or sombre defeat. Flanking these resting places are miniature pavilions with domes; they are surrounded by white rectangles made from cloth supported by twigs — sobering symbols of lives lost and the unpredictable designations of mortality.

Despite this unique mixture of melancholy and beauty, sobriety reigns. Of course, the obvious euphoria of discovery overrides every other emotion. Lucknow is a city that lives and breathes in such possibilities where a monument or elusive corner of its expanse can prompt an awakening for its discerning residents. Going further than the limitations imposed by acquired knowledge is always a source of deeper reckoning. This garden that houses nature and ghosts of mortality in its inner sanctum gives me another reason to keep my curiosity intact.

[1] Ghazi-ud-Din Haidar Shah (1769-1827), The first King of Oudh and the last Nawab Wazir of Oudh. He started a line of kingship which ended with the exile of Wajid Ali Shah(1822-1887).

[2] Traditional natural ingredients, often dyes or pastes from plants, used for coating buildings in Lucknow

Prithvijeet Sinha is an MPhil from the University of Lucknow, having launched his prolific writing career by self-publishing on the worldwide community Wattpad since 2015 and on his WordPress blog An Awadh Boy’s Panorama. Besides that, his works have been published in several journals and anthologies.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International

One reply on “Where No One Wins or Loses a War…From Lucknow with Love”

[…] Where No One Wins or Loses a War…From Lucknow with Love […]

LikeLike