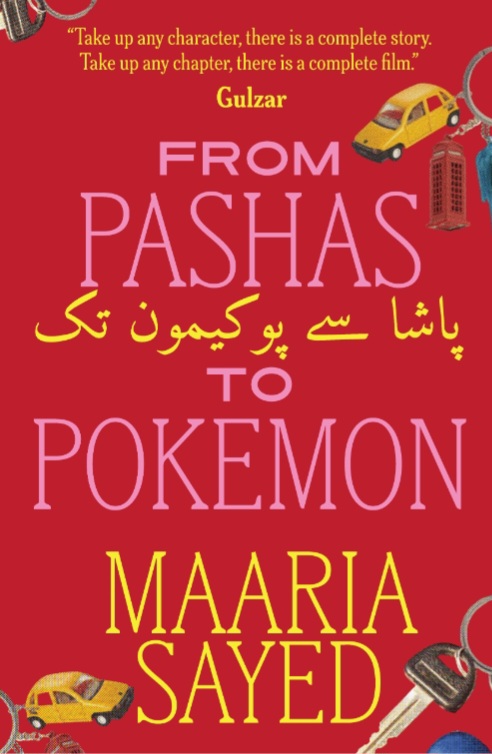

Title: From Pashas To Pokemon

Author: Maaria Sayed

Publisher: Vishwakarma Publications

Both the doors were locked. We knew Ammi must have locked the main door on her way out, but the emergency door wasn’t opening either. Yusuf and I jumped into our flat through our exceptionally large windows. We were accustomed to swiveling our fingers until we reached the latch hidden on the inside of the window. We’d pivot the hook and squeeze our pinky fingers through the tiny hole between the plastic orifices in the windowpane. Ammi had gone over to Nani Jaan’s house, and we were not expected back for another few hours. Rashid, my brother’s friend was reprimanded by his mother and grounded in his house to study. There was a limit to how much time Yusuf and I could spend at Rashid’s house eating sev puris with his mother. We sighted an excuse to get away and return home. But as Abbu says, fate has its way of creeping into the unlikeliest of places, so it did. The sunset remained hidden behind the mass of clouds, just like the rest of the month of November, and brought with it its own woes. Yusuf and I had expected to be jumping into an empty house, but were taken aback to see our living room filled with a score of giant men dressed in white kurtas. Abbu sat at the centre looking disheveled in his unkempt hair and crumpled lungi. It was an oddly monstrous sight. We had never seen so many men gathering at home when it wasn’t an Eid celebration. We were also not accustomed to seeing men with beards as long as these men had.

Nani Jaan had a personal assessment about the length of men’s beards that we had internalized over the years. ‘When it is longer than your fist, you know the intention is intimidation,’ she’d say in a spinechillingly confident tone. ‘We don’t live amidst Jalaaluddin Rumis and Nostradamuses anymore. The only inspiration the men could possibly be hiding under their beards would be a horde of lice.’ Thus, I had developed a quaint habit of mentally calculating the length of the beards I saw as I walked. Within the split second when I glanced around our living-room, I knew all their beards were much longer than their fists. I wondered how Abbu fit in with this forest of mens’ hair, because Abbu always remained clean-shaven, save the Sunday stubble Ammi would pester him to get off. On that particular day too, Abbu’s facial skin remained exposed.

The visual was threatening far beyond the beards when we saw what the men were concealing below their cloth bags and our pillow covers —— big black and brown guns. On our news channels, such guns were called AK 47s —— Yusuf identified the type almost instantly. We looked at Abbu helplessly, rummaging up a response, a conjecture, a remark, hint, and something —— anything. My single most gigantic fear was that Abbu was in deep trouble. Yusuf looked at me from the corner of his eye, gesturing to me to be tight-lipped and non-reactive. Abbu stared at us pale-faced, without uttering a word. He introduced us in a point-blank manner as his children.

‘Here, Yusuf is the naughty one I’d told you about. And his elder sister, my first born, Aisha.’ Abbu pointed at me and his index finger poked me like the razor-sharp edge of the blade Ammi used to carefully slice the dead skin off her feet.

Both Yusuf and I hated being introduced to the strangers we clearly despised. We took a seat in the corner of the room as Abbu directed us to. The next few minutes were a blur as my mind wandered into nothingness, like the blurry images of a super eight camera unable to focus on any particular sight. It just moved from beard, to table, to Abbu, to slippers, to window, to teacup, and back again to the beard. The next few moments were nauseating, like the time I tried my first mushroom drug. It was in an open field, a few hours away from Mumbai, on top of a blue car bonnet. I felt my shivers as I cascaded back and forth, breaking the continuum of time and space. I was sick for the next few days, but all Abbu and Ammi ever knew was that I had terrible food poisoning. Whenever Yusuf uttered the word mushroom in front of our parents to provoke me, I simply smiled, knowing that Ammi had decided never to cook mushrooms at home ever again. Abbu had subjected me to a sly smile as if he were fully cognizant of what was happening to me. Like various other things in my family, this was another one we buried under our carpets so I could sleep peacefully.

The bearded men bid their salaams to Abbu, smiled at us coldly, and hid their guns inside their oversized black kurtas before they left our home.

I was sixteen, Yusuf was thirteen, and we had seen what most people never get to see in a lifetime. Abbu forbade us from asking questions, demanding answers, or telling anyone what we had seen, ever. When we asked Abbu if Ammi knew what he was up to, he asked us to abide by our oath of complete silence regarding what we had witnessed. As anxious, hormone-charged teenagers, we naturally argued our way through the conversation with Abbu. He sat on the edge of the sofa, staring at the floor like a victim with nothing to back up his conscience. When Yusuf saw a discreet tear trickle down Abbu’s cheek, we stormed out of the room with an uneasy feeling eating away our guts. We loved to drive our parents up the wall, so long as we knew it was our doing. But the moment we sensed the involvement of another hand, it made us lament uncontrollably. Abbu and Ammi’s story about their engagement period was folklore for us. In our heads, they weren’t three-dimensional beings like the rest of our family. I clearly recall the morning Abbu, Ammi, Yusuf and I tried making pancakes for the very first time after Abdul Chachu, Abbu’s cousin, had written to us saying it was their daily breakfast ever since they relocated to Detroit. Of course, Abbu had responded saying he didn’t fancy pancakes, but nudged Ammi to hunt for the recipe since he desperately wanted to taste what his cousin had substituted scrambled egg with. Pancakes, in Abbu’s mind, became the recipe to success; he envied how his cousin had started from scratch and managed to make a respectable living in a foreign land. That morning, when we ate pancakes for the very first time, we looked at each other, trying to gauge if the one seated opposite us really liked them. Ammi sat opposite me and I remember seeing her gulp hers down with long sips of sherbet. We all disliked them, but we never admitted this to each other. Probably the one who disliked them the least was Yusuf, but I could tell that he would never substitute our scrambled eggs for what seemed like a cross between South Indian dosa and Maharashtrian pooran poli with a whole lot of Nutella.

ABOUT THE BOOK

At 25, Aisha has seen more than many people do in a lifetime and has understood one thing: no matter who you are and where you are from, there are things that you can study and others that you can actually learn from and grow.

Lively tales from family history and everyday life in a Mahammad Ali Road colony in Mumbai form the background of Aisha’s internal journey. Childhood memories mingle with her experiences while studying in London, and are woven into a sharp commentary on the transformations in India over 20 years as she ponders her place in this ever-changing world. The novel narrates the story of many journeys. It is a journey of growing up: the journey from childhood to adolescence, youth to old age, from one culture to another, and a glimpse of past to present times.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maaria Sayed is an Indian filmmaker and writer whose work focuses on the sexual and spiritual liberation of women, evolving Muslim identities, and South Asian life. She has been supported by Cineteca di Bologna, Sharjah Art Foundation, and Busan Film Commission, among others, and was a delegate and jury for the UN-backed Asia Peace Film Festival in Pakistan. She regularly holds workshops on cinema for students and teaches intercultural communication to executives of multinational companies. She is a graduate of literature and cinema, and obtained her fellowship on Asian media production and collaboration in South Korea. She is passionate about Sufi poetry, folk music, Indian theatre and cats- big and small. This is her debut novel.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International