By Wayne F. Burke

Norman Perceval Rockwell went into dementia in the last years of his life and died at 84 in 1978. He was a deeply insecure human being—about himself and his work. Even as a cultural icon, he still distrusted his judgement, wondering if the quality of his work was slipping, if editors would still take it, if he and his work were passé—too old fashioned. His insecurities—masculinity among them; his struggles with self-worth and the worthiness and meaningfulness of his work, drove him to achieve a kind of surface perfection in his work and self.

He wore rose coloured glasses an inch thick, refusing to acknowledge the seamier side of life, though in a few pictures, very few, he stepped out of character: with a poster/picture of a machine gunner, 1942; with a 1960’s painting of a little black girl being escorted by U.S. Marshalls, he presented a deeper reality, clearer vision, than his usual joshingly superficial emotionalism—the signature of his work. His seven years in therapy with Eric Erikson did bring a deeper psychological nuance to his work, but the depth remained at the shallow end of the pool.

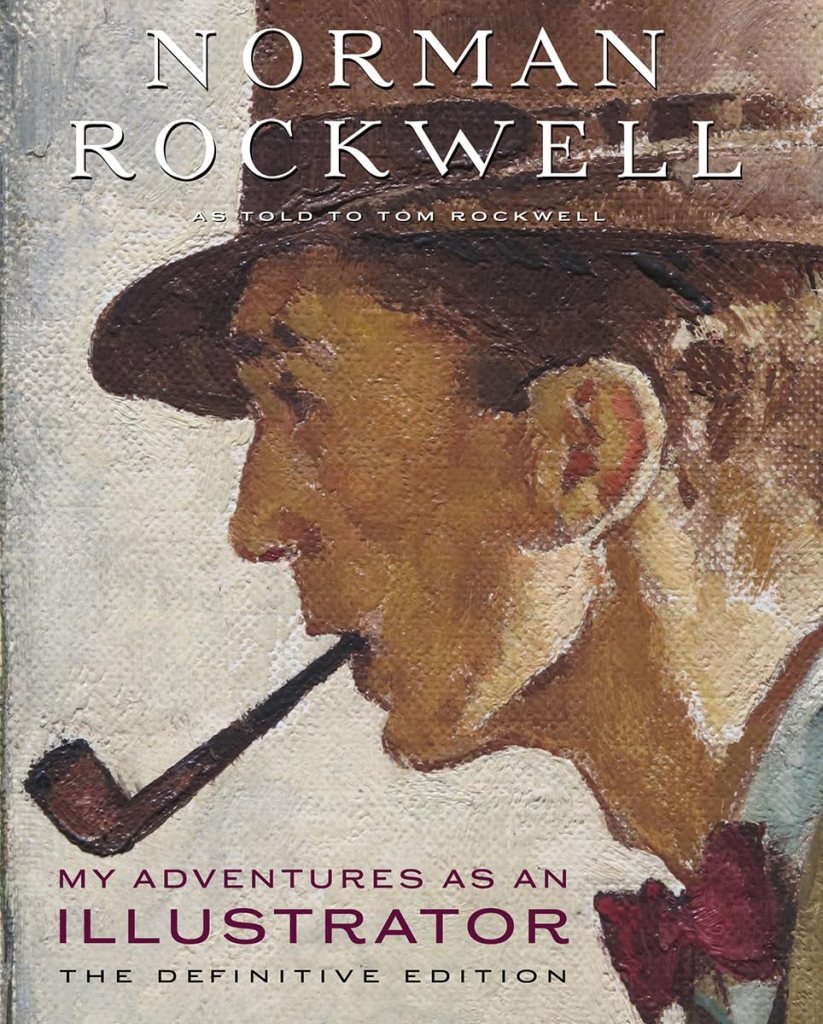

“I have the ability,” he wrote in his autobiography My Adventures As An Illustrator,“to ignore unpleasant or disturbing experiences.” (In the autobiography, he failed to mention his second wife’s alcoholism—they were married for twenty years.)

He remained blinkered to reality, setting out purposely to create an alternative and prominently adenoidal looney-tune world.

As a product of a valetudinarian mother and a cold remote father (a salesman) Norman became an emotionally stunted pedantic oddball whose work straddled worlds of illustration and fine art. Whenever asked, he always declined to describe himself as an “artist,” insisting he was an “illustrator.” A display of humility, Deborah Solomon noted in her Rockwell biography, or a defensive feint—“he couldn’t be rejected by the art world if he rejected it first” (American Mirror, ‘The Life and Art of Norman Rockwell’). The insipid emotionalism of his characterisations ensured his place as illustrator.

Though Americanising Dutch Realism, as Solomon also noted, his technique—fidelity to realism, and to the shallowness of his vision—made his work’s elevation to rarified “art” probable though only as a side-show, as an art of eccentricity, and not for the big tent.

Wayne F. Burke is, primarily, a poet–with 8 published poetry collections to date–but also writes prose fiction, nonfiction, and expository. His most recently published book, a nonfiction work, is titled “the VAN GOGH file: POTATO EATERS, PREACHERS, AND PAINTERS,” Cyberwit.net., publisher. He lives in the state of Vermont (USA).

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL

Click here to access the Borderless anthology, Monalisa No Longer Smiles

Click here to access Monalisa No Longer Smiles on Kindle Amazon International