Dr Meenakshi Malhotra delves into the relevance, history and iconography of Kali as we draw nearer the date of Diwali and Kali Puja

Kali Puja, a festival that celebrates the defeat of a demon in the hands of a dark goddess Kali, is celebrated in Bengal and some other parts of India on the new moon day of the Hindu month of Kartik, and coincides with one of the biggest Hindu festivals in India, Diwali. It usually falls around end of October or early November. Kali Puja is performed to signify the victory of good over evil, and the celebration is geared to seek the help of the goddess in destroying evil. Although Kali was present in mythology and some scriptures, she was on the margins of the spectrum of Hindu goddesses. Kali-worship was popularised by Raja Krishnachandra of Krishnanagar in Nadia(Bengal), only around the 18th century or so. By 19th century the family and community worship of Kali became an annual event, much like the event of Durga-worship under the patronage of elite and wealthy families. It coincided with a resurgence of Hindu revivalism in 19th century Bengal, which was fuelled in part by a perceived threat to Hinduism by imperialism and colonialism.

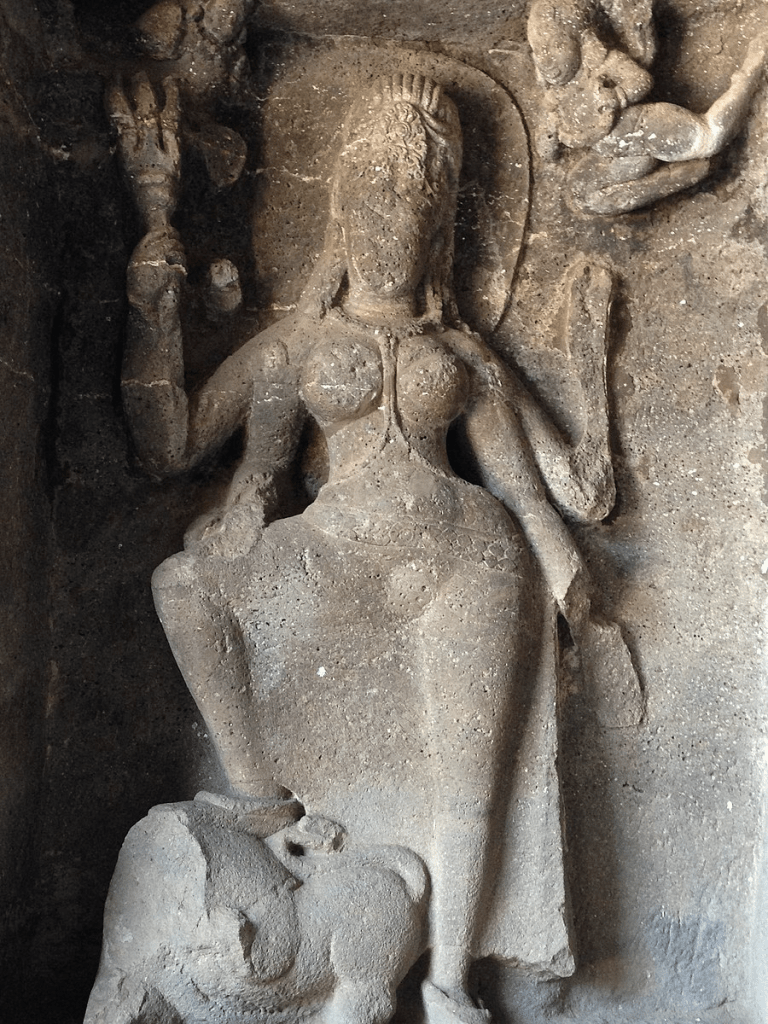

Kali is perhaps the most mystifying in the Hindu pantheon of gods and goddess. Evoking deep devotion in her devotees, she represents a vision and spectacle which is truly terrifying. Kali represents an eternal puzzle and an enigma to scholars and rationalists. Represented as standing upon Shiva and wearing a necklace of human heads, she represents the image of the divine mother as dark and destructive, cruel and cannibalistic.

Perhaps we need to recapitulate the history of the goddess’s representation in various religious texts that she appears in. The Agni-and Garuda Puranas record that her worshippers petition Kali for success in war. In the 5th segment of the Bhagavata Purana, Kali is represented as the patron saint of outlaws, who invoke her in fertility rites that involve human sacrifice, according to David Kinsley in his book on the Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition.

Banabhatta’s 7th century drama Kadambari contains a similar story featuring a goddess named Chandi, an epithet used for both Durga and Kali. A tribe of hunters worship Kali, plying her with ‘’blood offerings”. According to David Kinsley, this pattern of representation appears in numerous other texts. In Vakpati’s Gaudavaho, a historical poem of the late 7th and early 8th century, Kali is portrayed as clothed in leaves and as one who accepts/receives human sacrifice.

In Bhavabhuti’s Malatimadhava, a drama of early 8th century, a female devotee of Chamunda, often identified with Kali, captures the female protagonist, Malati, with the intention of sacrificing her to the goddess. Like Kali, Chamunda is depicted as a terrible goddess, a maternal dentate, “a mother goddess with a gaping mouth and bloody fangs”. One hymn praising Chamunda describes her as “dancing wildly and making the earth shake” just as Kali did while defeating the demons who threatened to destroy the cosmos. Another text is Somadeva’s Yasatalika (11th-12th century)which describes a goddess Candamari whose iconography seems remarkably similar to Kali’s. Candamari is described in the 11th century text referred to above as a goddess who adorns herself with pieces of human corpses, uses oozings from corpses for cosmetics, bathes in rivers of blood, sports in cremation grounds and uses human skulls as drinking vessels. Bizarre and fanatical devotees gather at her temple and undertake forms of ascetic self-torture.

In the pantheon of Hindu goddesses, Kali represents a force that is disruptive, wild and uncontrollable. She threatens stability and order and when she kills and subdues demons, she becomes frenzied and drunk on her victims’ blood. Untameable and liminal, Kali is cast in the image of a mother goddess who resolutely resists domestication.

We notice a resurgence of Kali worship in 19th century Bengal. While Kali and other Shakti goddesses are worshipped in some parts of India like Bengal and Himachal and in Nepal which borders India on the north east side, many of the Hindus of northern India worship the gods of Vaishnavism, like Krishna. In the south, the sects of Vaishnavism and Shaivism accord primacy to Krishna and Shiva, respectively.

The British had colonised most of India by the second half of the 18th century. By late to mid-19th century, imperialism had led to a burgeoning critique of colonialism and the beginnings of nationalism, catalysed by waves of social reform, particularly in Bengal, Maharashtra and Punjab. While the worship of the fair, refulgent, glorious and most significantly, domesticated, figure of the goddess Durga was started and encouraged to provide a platform for the Bengali community to come together — a similar function was performed by the worship of Lord Ganesha in Maharashtra — Kali worship came to be practised by more subordinated social groups. She acquired respectability and recognition among educated middle-class Bengalis when she became the central figure in Hindu revivalism led by Ramakrishna Paramahansa (1835-1885). One reason for this phenomenon that promoted and made Kali worship respectable in the late 19th century, was the emergence of a new sect that, merging classical Hinduism and other forms of worship like Tantrism (a school of Hinduism which believes in the practice of some secret rituals to gain knowledge and freedom), rejected dualism.

Ramakrishna Paramahansa who was at the forefront of this phenomenon was a mystic and ascetic who was dedicated to Kali-worship, and whose devout practices offered devotees a space outside the domain of colonialism, which in turn helped trigger a Hindu revival. For the middle class Bengali functionaries who were in the lower rungs of colonial service, their subservience might have proved emasculating, a thesis argued by Sumit Sarkar, Mrinalini Sinha and others. In this context, it could be speculated that Kali’s fierceness, her performance of virile masculinity might have helped her devotees reclaim a sense of manliness by associating themselves with her masterfulness.

Another reason Kali worship became especially popular among militant nationalists, criminals and outlaws, forest dwellers and tribal populations, and emerging fringe groups was because they discovered in Kali a powerful resource for protesting against their impoverishment and downtrodden status. Kali was also seen as a way of articulating their aspirations for political empowerment. As a mother goddess associated with fertility, birth, creativity as well as violence and martial prowess and anger, Kali offered the nationalist movement an apt narrative and iconography. It is a well documented fact that Kali-worship increased in Bengal in the 1890s and the first decade of the 20th century, along with the rise of extremist and militant nationalisms.

One of the first novelists in India and the foremost novelist of late 19th century Bengal who was instrumental in the rise of the novel in India , Bankim Chandra Chattopadhay (1838-1894) describes Kali in his novels is a signifier of Hindu cultural nationalism. In his political novel, Anandamath, he uses Kali to signify ‘time’(Kala)and political change. According to critics like Jasodhara Bagchi, Bankim departs from classical and medieval Indian literary conventions. They see Bankim’s use of the iconography of Kali as reflective of a modern, secular, rationalist sensibility. However, Bankim did not believe that Indians would rally behind a secular independence movement. Instead he felt that a sense of nationalism could best be cultivated through religion in the Indian context.

Bankim also believed that women and the feminine principle are particularly powerful forces for social change. He equated the nation with the divine maternal and asserted that the homeland or motherland should be the object of devotion. This adaptation of Shakti’s mythology to the Indian nationalist project lent the figure of the mother goddess a new militancy.

In the novel Anandamath (literally meaning ‘abode of joy’) Kali’s darkness signifies India’s degradation at the present time. In ancient times, the ‘mother’ was glorious and resplendent. In the present, Satyanand , one of the characters in the novel, says, “look what the mother has come to…Kali, the dark mother. Kali is naked ,” he adds , “because the country is impoverished, the country is now turned into a cremation ground, so the mother is garlanded with skulls.” This is however a temporary state because the monk believes that the goddess and motherland will be restored to its previous glory, rescued by her brave sons.

Bankim develops the idea of linear time, past-present-future, which is tied up with his idea of writing a history of Bengal. Kali gets linked to evil, to political action but also to the idea of temporality–‘kala’, which literally means an epoch- and more importantly, the idea of apocalypse. Kali’s stepping on Shiva is seen as a reversal, a turning upside down of the accepted order of things. For Bankim who was a functionary in the colonial government, this vision of a world upside down had its use in restoring one’s self-respect.

In the late 20th century, Kali was again invoked as a vital part of right wing assertion and the rise of Hindu nationalism of the 1990s.The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (World Hindu Council) called its women’s wing ‘Durga Vahini’ (the carriers of Durga’s lore), which was established in 1991,invoking the names of Durga and Kali to signify cultural assertion of Hindu womanhood. However, the women’s movement in the 1990s found that the “ ‘Shakti of the modern Durga’, was not directed against violence in the home and community but was directed externally to the Muslims-both men and women…the myth that all women are equal and could be mobilised around a common issue on a common platform lay shattered” (Sarkar and Butalia,1995)a point that gets reinforced time and again. Flavia Agnes, a lawyer who works on issues of women’s rights, indicates her discomfort with Kali as an emancipatory trope for all Indian women as it remains essentially Hindu and does not accommodate women from other religions and communities. Kali or the dark goddess as a pan-Indian figure of empowerment for all women remains problematic, as it is too exclusionary and mired in violence.

Where there might be a tiny sliver of a possibility of reclaiming Kali as an emancipatory idea or a figure of emancipation might possibly be in two areas. One is to break the deadlock of ‘fair and beautiful’ in Indian culture, the prevalence of gender stereotyping of a reductive kind. Here, dark skinned girls carry a sense of social stigma and are often, in media representations, encouraged to use products that would lighten the effects of dark skin, both to improve their prospects of a glamorous career and a decent marriage. The other maybe to do with the idea of motherhood which is made more complex. While Durga rather than Kali is associated with motherhood, Kali as mother maybe reclaimed as a mother who does not necessarily shield her children by sugar-coating reality, but introduces them to death, destruction and the existence of ultimate reality. That is the significant moment in the iconography of Kali — the moment when she steps on Shiva, her consort, who is also the Lord who presides over destruction, in the Hindu trinity of Brahma-Vishnu-Maheshwar(another name for Shiva). Her tongue pops out as she is caught in this stance of utter surprise, frozen in eternity(in her representations) even as she presides over time(kala).

References:

Bagchi, Jasodhara(2008) Positivism and Nationalism:Womanhood and Crisis in Nationalist Fiction-Bankim Chandra’s ‘Anandamath’ Women’s Studies in India: A Reader ed Mary E.John, Penguin, pp124-131.

Chattopadhyay, Bankim Chandra(2005)Anandamath or The Sacred Brotherhood, translated by Julius Lipner, OUP

Kinsley, David(1986) Hindu Goddesses:Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition, Motilal Banarsi Das

Sarkar, Sumit(1998) Renaissance and Kaliyuga:Time, Myth and History in Colonial Bengal in Writing Social History. OUP,186-215.

Dr Meenakshi Malhotra is Associate Professor in English at Hansraj College, University of Delhi. She has edited two books on Women and Lifewriting, Representing the Self and Claiming the I, in addition to numerous published articles on gender and/in literature and feminist theory. Some of her recent publications include articles on lifewriting as an archive for GWSS, Women and Gender Studies in India: Crossings (Routledge,2019),on ‘’The Engendering of Hurt’’ in The State of Hurt, (Sage,2016) ,on Kali in Unveiling Desire,(Rutgers University Press,2018) and ‘Ecofeminism and its Discontents’ (Primus,2018). She has been a part of the curriculum framing team for masters programme in Women and gender Studies at Indira Gandhi National Open University(IGNOU) and in Ambedkar University, Delhi and has also been an editorial consultant for ICSE textbooks (Grades1-8) with Pearson publishers. She has recently taught a course as a visiting fellow in Grinnell College, Iowa. She has bylines in Kitaab and Book review.

.

PLEASE NOTE: ARTICLES CAN ONLY BE REPRODUCED IN OTHER SITES WITH DUE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT TO BORDERLESS JOURNAL.

2 replies on “How a Dark Goddess Lights up a Fallen World”

My mother tells me that when I was a baby, my grandmother used to bathe me while she recited ‘Shyama Ma rone metechhe, Shiber buke paa diye jeeb ketechhe’ … I love to think that she was blessing me to grow up to be unconventional !

LikeLiked by 1 person

The misunderstood and misintrepreted image of Kali has very well been washed away by the logical and rational explaination in this article. Another amazing piece mam @DrMeenakshiMalhotra.

LikeLiked by 1 person